DAVID FITZGERALD & THE FENN FAMILY IN TEXAS

Marker is located on the east bound side of State Highway 6 at the intersection of Post Oak in Arcola, Texas.[2008]

The Fitzgerald and Fenn Fanilies David Fitzgerald, a veteran of the American Revolution and the War of 1812, came to Texas from Georgia in 1821. His son-in-law, Eli Fenn, followed in 1832. Fenn served during the Texas Revolution amd signed the 1837 petition for the creation of Fort Bend County. An expert in natural remedies, his wife Sarah aided sick residents. One of their sons, John R. Fenn, was a war veteran, Duke's first Postmaster and a businessman. His wife, Rebecca [Williams], was a charter member of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas. F. M. O. Fenn, John and Rebecca's eldest child, served as County Attorney and later as Justice of the Peace. In 1893, the Sons of the Republic of Texas organized in his office in Richmond. Sarah, John R. and Rebbecca Fenn are burried in the Duke Cemetery.

William Little John M. Little James Beard

Anahuac Disturbance Daniel Shipman James B. Miller

|

The error that changed local history David Fitzgerald arrived in this Mexican run territority of Texas in late 1821. He began building his home on property he wanted to claim. When he went to San Felipe to file his claim, Steven F. Austin informed him the League was already claimed by William Morton. William Morton agreed to trade David Fitzgerald 1/4 of his League for 1/4 of the League David Fitzgerald would claim, thus allowing David to own the home he was building. David Fitzgerald claimed his League 20 miles downstream on the Brazos River. The trade was not immediately recorded, mainly because the area belonged to Mexico and recording land transactions was difficult. David died in 1832, shortly after participating in the battle of Annahuac. William Morton drowned in the Brazos River in 1833, leaving a wife, Nancy, two sons, John V., amd William P. Jr. and two daughters Louisa Ann and Mary. David's daughter, Sarah, married Eli Fenn and they continued to live in the home David built. The decendents of the Fitzgerald and Morton famlies eventually filed the land transaction for the 1/4 League trade. The Morton familly lived on the west side of the Brazos River until the death of William, when Nancy moved the family to the east side of the river closer to the Fenn family. Nancy sold the property on the west side to developers who would create Richmond, Texas. Louisa Ann Morton married Daniel Perry on December 24, 1833 and they moved to the land obtained by the 1/4 League trade [the Duke area] in 1834. In 1836, after the fall of the Alamo, General Santa Anna chased General Sam Houston causing the settlers to flee in what is known as the 'Runnaway Scrape'. The Morton and Fenn homes were destroyed by the Mexican Army. Both families relocated on the Fitzgerald League. The Fenn family lived with Moses Shipman until they completed their new home. The Morton family lived with Daniel and Louisa Ann [Morton] Perry on the 1/4 League they had gained by trade. Also in the year of 1836, John V. Morton married Elizabeth Shipman, they were the son and daughter of two 'original 300' settlers. Because David Fitzgerald built his home on land that wasn't his, an agreement to trade 1/4 League with William Morton was formed with the traded land became the new home for the Morton family after the Mexican Army destroyed their previous home. |

THE COMPLETE STORY

By Mona M. Fenn

David Fitzgerald was over fifty and a widower when he came to Texas late in 1821. Previous to that time he had been a Georgia planter. He would become one of Austin’s “Old Three Hundred”. His daughter, Sarah, would marry Eli Fenn. The purpose of this material is to discuss their lives and the lives of their descendants in Texas. But, we will begin in Georgia. For many years, Indian tribes all over the continent had been resisting attempts by the European settlers to remove them from their land. During the War of 1812, which was a dispute between colonists and England about borders and ocean shipping rights, some tribes sided with the British. They wanted to gain a new homeland for all Indian tribes. Among the five southeastern tribes, two carried out organized rebellions against U.S. Forces. These were the Creek and Seminole. We are interested in the Creek War of 1812-14 because of Fenn involvement. Eli Fenn’s parents and grandparents had moved to Georgia from North Carolina in 1793, and he was born there the next year. During the War of 1812, Eli, age 18, served in the Georgia Militia Volunteer Riflemen; and so did his father, Willoughby. Serving with them was David Fitzgerald.

After an attack by the Creek Indians on Fort Mims, on the Alabama River, an army of 3500 was organized under the leadership of General Andrew Jackson. In March of 1814, Jackson approached the Creek fortification at Horseshoe Bend. This was a peninsula on the Tallapoosa River where the Indians had built a zigzag double-log fort. Jackson had his troops surround the Indian positions on both sides of the river, remove the canoes the Indians planned to use for their escape, and then attack. After a day-long battle, Jackson’s men were finally able to set the barricade on fire and gain victory.

Belle Fenn Clark’s application for Daughters of the War of 1812 membership, #407-8368, says that during the War of 1812, Eli became a close friend of Andrew Jackson and served with him in the famous Battle of the Horseshoe on the Tallapoosa River in Alabama.

After the war, and before 1820, Willoughby and his family, including Eli and other children, moved from Georgia to Mississippi. Their trip followed an Indian trail, the ‘Three Chop Way’. They took what they could on a pack horse, leaving all of their furniture in Georgia. A half-breed Indian helped them across the Tombigbee River and told them to stay in his hut because he was going to a dance. They didn’t see anyone with white blood again until they reached Woodville, Mississippi. They settled in Lawrence County, where they farmed, and where the family of eight was on the 1820 census.

A man named Moses Austin had been an importer in Philadelphia and a lead miner in Virginia. In l797, after learning of the rich lead deposits in Missouri, discovered by the French, he went there and obtained a grant from the Spanish. He brought his family, including son, Stephen F., and thirty others. Under his leadership, the mining and smelting of lead changed from the primitive methods of the French into Missouri’s first major industry. Austin built a magnificent frontier mansion, a store, flour mill, blacksmith shop, bridges, roads, a shot tower, etc.

The War of 1812 cut off Moses Austin’s outlet to eastern markets, and then a general depression made recovery impossible. In 1819, there was a panic when banks failed. Austin had invested his mining fortune in a banking venture that was not successful. He was financially ruined, and he lost all of his properties

With hopes of recovering his fortune, he went to Texas in November, 1820 and obtained permission from Spanish authorities to settle 300 families in Texas. After he returned to Missouri, he died in June of 1821. His son Stephen F. would carry out the plan to colonize Texas.

David Fitzgerald, in Georgia, must have had misfortunes similar to those of Moses Austin, although probably not of the same magnitude. He must have seen advertisements about Austin’s plan, although we do not know that he actually knew Austin. Ms. Pickrell says, “David Fitzgerald fell under the magnetic power of Moses Austin and decided to join him in his efforts to colonize Texas with people of the Anglo-Saxon race. The death of Moses Austin failed to check the enthusiasm awakened by this illustrious man. Stephen Austin took up his father’s work, and David Fitzgerald, with his family, was forever thereafter numbered among the 300 famous in Texas history.”

Moses Austin was 59 when he made his trip to Texas seeking permission from Spanish authorities to establish a colony there. The Spanish Governor, Martinez, told him that a port of entry was to be opened at the mouth of the Colorado River (now Matagorda), and he suggested that Austin locate his settlement there.

Both going and coming, he had crossed the Colorado at Bastrop; but he had not been to the mouth of the river. However, he wrote to his son, “On the bay of San Bernardo, the harbor is good, 12 feet of water over the bar and 25 to 30 feet up the river for miles. The Governor has granted me permission to locate a town there.”

According to Mr. Wharton, this is strange because there was then and had been for centuries a raft of drift which filled the mouth of the Colorado and made it difficult, if not impossible, for boats to enter. DeLeon saw it in 1690. It was there until 1925 when it was removed by the people of Wharton and Matagorda Counties. It seems that Governor Martinez and other Spanish authorities did not know this, and Austin did not see it.

In July, 1821, after his father’s death in June, Stephen Austin wrote that he was on his way to Texas to take charge of the land granted to his father. “It lies on the Brazos and Colorado and includes a port of entry on the bay San Bernardo” (mouth of the Colorado). About 20 men were with him. After visiting San Antonio, they went by Goliad down to the coast and crossed the Colorado15 or 20 miles above the bay. Tired and in a hurry, they did not go down to the port of entry they had come to see. But, having looked across the boundless Gulf for days, they knew what San Bernardo looked like.

Austin was anxious to get back to Louisiana and get his emigrants moving. In September, when they reached the Brazos somewhere below Columbia, he chose as one his locations the leagues later granted to Bell and Varner. Going up the Brazos, they crossed it somewhere above Big Creek and below the Big Bend.

William Little and the Lovelace brothers saw this beautiful landscape in September, and in late November, while the Lively was officially headed for San Bernardo, these men were bound for the bend in the Brazos.

In November, in New Orleans, Austin made final plans. One group of immigrants was to take the overland route with him. The second group was to go by boat, a schooner, the Lively, and take the heavy load of supplies that would be needed to make a permanent settlement.

Austin told the crew of the Lively to enter the mouth of the Colorado and wait for him to come overland and guide them to the colony. They sailed in November with 18 colonists on board. The schooner encountered a gale that blew for 36 hours, and it was tossed about for four weeks. On Christmas Day, 1821, the mouth of the Brazos was sighted, and the Lively landed there. It left about 15 men with their supplies, farm implements, and a rowboat.

Stephen Austin, coming overland, crossed the Brazos at the site of future Washington-on-the-Brazos and found Andrew Robinson’s family and others camped there. He went on to San Bernardo to meet the Lively; he waited three months, but it never came. During that time, it had disappeared on a return voyage.

The new arrivals at the mouth of the Brazos saw no signs of life. They saw a beach that stretched inland without shrubs or bushes and the mouth of a river. They might not have been sure where they were or where Austin might be. They might even have thought that this was the Colorado.

They camped on the west bank of the river but soon moved upstream to a cottonwood grove. Using the rowboat, some of them made a six-day journey up the river, going as far as the big bend. They did not find Austin or the overland colonists, so they returned to the mouth of the Brazos. Wharton’s book says, “It has long been told that Austin told them he would meet them there (the Big Bend) and that this is why they left the Lively. In the first advertisement of Richmond in 1837 it is stated that Austin instructed Little to go there.” (Evidently there was some miscommunication.)

Although the group wanted to go further inland, one rowboat obviously would not carry all of them plus their ton of farm tools. They found an old walnut log canoe, repaired it, and worked on other boats.

After three weeks, their supplies were running low. Then one day, according to Mr. Creighton, a man named Fitzgerald, with a party of four, came into the mouth of the river in a 40-foot pirogue. With the addition of this serviceable craft, they were able to begin their journey up the river.

A pirogue is a flat-bottomed dugout, propelled with poles, designed for marshes and shallow water. The Lewis and Clark Expedition of a few years earlier, 1803-05, used large pirogues which, possibly, were not dug-outs at all, but big flat-bottomed, masted rowboats built from planks.

In late February or early March, they reached a place where the river formed a high bluff with a rolling prairie beyond it. Perhaps recognizing this as their destination, they stopped. There was a prairie to the west and rich lowlands bordered by canebrakes to the south. At this spot, near what is now Richmond, they began to make a settlement. They cut trees, notched logs, and built a 20 or 24 foot square fort—to become known as Fort Bend. They also planted corn, but the weather was too dry; it did not produce a crop.

Some of the men went back down the river hoping to find some news of Austin. Instead, they found William Morton, who had sailed with his family from Mobile, Alabama. Their boat wrecked on Galveston Island, and Morton and his son went in search of help. The group from the Lively went with him to help rescue his wife and five daughters. During the rescue, two of the Lively men drowned, but the women were saved. The entire group went back up the river.

After the failure of their corn crop, the immigrants became discouraged, and some of them returned to the states. Of the original Lively group, only William Little, James Beard, and James A.E. Phelps stayed; and with Morton and Fitzgerald, they would be part of the ‘Old 300’.

When David Fitzgerald first arrived at ‘Long Reach’ on the east bank of the Brazos River about 19 miles below the present town of Richmond, a small band of Indians had a cluster of wigwams there. They fled at the sight of Fitzgerald’s group, and they did not return.

Fitzgerald did have another experience with these, or other, Indians during the early settlement of the area. This must have happened on the quarter of the Morton League he would have near Richmond. Mr. Sowell tells the tragic story of a tribe of ‘Coast Indians called Kraunkaways’, who made a raid on some of the colonists, killed some of them, and took a little girl captive. After fleeing some distance, they camped, killed the child, and were eating her when they were taken by surprise by a group of settlers, including Fitzgerald, who had been trailing them. During the fighting, all the Indians were killed except a squaw and her two small children, who ran away. At the house of Jack Randon, near present Richmond, the squaw made signs of hunger to Mrs. Randon who had her cook give them food. The squaw then took her children to the shade of a nearby tree. When some white men came to the house, Mrs. Randon told them what had happened. According to Mr. Sowell, these men felt that “it was best to exterminate such a race, and killed all three of them. John R. Fenn (Fitzgerald’s grandson) saw the bones of these ‘unfortunates’ scattered around the tree when he came to the area later.”

Upon arriving in the area, Fitzgerald and the other settlers knew that clearings had to be made and crops planted. The river bottoms were covered with cane; and this was cut down with heavy knives or hatchets and allowed to remain there until dry; then it was burned. When planting time came, holes were made in the ground with spikes, corn kernels were dropped in, and soil was pushed over them with the foot. The corn came up and grew well. When the cane grew back up and began to crowd out the corn, it was knocked down with sticks.

When the corn began to mature, the bears were so numerous that they would have eaten all of the corn if Fitzgerald had not furnished his men with a gun and a pound or two of ammunition and instructed them to ‘make war on the bears.’ They, however, were bad marksmen, and shot away all of the ammunition and only killed one bear—using this plan: In felling the trees to make a clearing, a large one had fallen in such a manner that one end of it was inside the field and the other end was on the outside. At that spot, an old bear came into the corn by walking this log. One of the men heavily charged the gun, positioned himself at the end of the log, inside the field, pointed the gun along the log, and waited for the bear. When it came and mounted the log, it walked straight toward the muzzle of the gun. Mr. Sowell says, “A terrific explosion was heard, almost loud enough to make every wild animal in the Brazos bottom for miles around start from his lair and pull his freight.” When the smoke cleared, a dead bear was beside the log; and a happy, but badly shaken up, man was not far from the end of it.

On another occasion, Fitzgerald’s men found a panther up a tree. One of them stood off a distance and shot at it. The panther was not hit, but came down and went up another tree. This was repeated about four times, and then the marksman stood at the root of the tree and fired straight up. This time, the panther was killed and fell to the ground. The man concluded that the way to kill panthers was to stand under the tree and shoot up at them.

When the English speaking colonists began to spread out across Texas, they found wild cattle from the Red River on the north to the Rio Grande on the south and from the Louisiana border on the east to the uppermost breaks of the Brazos on the west. The cattle did not run in herds but stayed in small bunches. They were wild and alert and fled at the sight of humans. Many of the settlers thought that the cattle were native to the area; they called them ‘wild cattle’. However, these cattle were descendants of those that were brought by Spanish explorers and missionaries as early as the 1500s. The same was true of the wild horses that were abundant. Cattlemen soon began to call the cattle 'Texas and then, 'Longhorns.’

Over in Mississippi, in 1823, Sarah, the daughter of David Fitzgerald, married Eli Fenn. He was 29; she was 26.

Many of the people who came to Texas at this time left debts and unpaid judgments behind. This was quite common because of economic conditions in the United States at that time. These people were interested in protection from debt collectors, and Stephen Austin succeeded in securing a homestead exemption law.

We (the family) do not know any details of the life of David Fitzgerald before he came to Texas, other than the military service mentioned. The HANDBOOK OF TEXAS describes him as a widower over the age of 50 and also quotes from THE AUSTIN PAPERS, p. 702, a letter from Stephen F. Austin to Luciano Garcia: “To preserve good order in the colony under my charge, I have been compelled to cause five men to leave it, with their families, to wit: Briton Baylie (sic), John M. Coy, Alen White, David Fitzgerald, and Daniel O. Quin. They are all men of infamous character and bad conduct, fugitives from the United States, one for having committed murder, the others for having counterfeited money, and for whose apprehension the American Government has offered high rewards. Men of such a stamp can not but be prejudicial to this new settlement; therefore, I hope that my action will meet your high approbation.”

Our research has not yet uncovered any details of the reasons Mr. Austin gives in the letter for expelling these men, nor has it found a response from Mr. Garcia. However, history does tell us that at least two of these men, Bailey (whose name Austin could not spell) and Fitzgerald, remained in the colony and became members of the Old 300.

James Briton (Brit) Bailey settled near the Brazos River in Brazoria County, and Bailey’s Prairie is named for him. According to the HANDBOOK OF TEXAS, he was “noted for his integrity, his fearlessness, and his eccentric behavior, which have made him a somewhat legendary character in his community.”

In 1824, in Mississippi, John Rutherford Fenn was born. His parents, Eli and Sarah, would bring him to Texas in about nine years.

The first settlers in Austin’s Colony in Texas are known as the “Old Three Hundred”. These were the families brought into Texas by Austin under his contract with the Mexican government (Mexico had won its independence from Spain.) The 300 families were all, or nearly all, in Texas before the close of the summer of 1824. The lands chosen by the settlers were the rich bottoms of the Brazos, the Colorado, and the Bernard; each grant contained about 4,428 acres. There were 307 titles issued with nine families receiving two titles each, which left, not including Stephen Austin, 297 as the actual number of families introduced under this contract. The original titles are now in the archives of the General Land Office at Austin: they are bound in volumes of convenient size. We (the Fenn family) have, in an Abstract of Title, a ‘correct, translated copy of the original title to David Fitzgerald existing in the Spanish Archives.’

David Fitzgerald at first wanted to locate his league at a location three miles below Richmond, but he found out that this land had already been chosen by William Morton. So, Fitzgerald’s grant was located 19 miles below Richmond at a place then known as ‘Long Reach’. One-fourth of a league of this land was exchanged with Morton for that amount on his grant near Richmond. (Keeping this in mind will help avoid confusion when events of 1836 are discussed later.)

In 1825, four years after the Lively passengers arrived at the mouth of the Brazos, Austin’s colony had a population of 1800 people. Bell’s Landing opened as a river port. A few years later, Columbia (now West Columbia) was founded two miles from Bell’s Landing. In 1826, Brazoria County’s cotton crop averaged from 2500 to 3000 pounds of seed cotton per acre, about two bales.

Eli Fenn, using a boat he built, and other area farmers, brought their cotton down the river to this port which was, at times, called Marion, Bell’s Landing, and Columbia. Mr. Sowell describes the technique of making lumber used by Fenn to build the boat he used in the 1830s: “The lumber from which this boat was made was cut by a whipsaw, the logs being raised on scaffolding, and the saw working up and down, one man being on top of the log and the other underneath. The boat could carry about 12 bales of cotton. Mr. Fenn would take a load of cotton to Columbia (now East Columbia) and bring back a load of supplies. Then he either loaned or hired the boat to Thompson for use as a ferry as he would not need it again until the next cotton season.”

For seventeen years, beginning in 1830, the Jesse Thompson ferry was operated on the Brazos, three miles northwest of Richmond, even though Jesse, himself, died in 1834. As we shall see, we do not want to confuse this location (Thompson’s Ferry) with that of Thompson’s Switch, the Santa Fe Railroad crossing nineteen miles below Richmond, which came later. (There was a ferry there also, but it did not cross where the railroad did, and still does. Thompson Ferry Road is behind what was once the town of DeWalt, which is no longer there.)

We mentioned ‘cane’ earlier; and an interesting description of cane brakes was given by a traveler to Texas in 1831. His name was not preserved with his writing, but researchers think it was Fiske. He said, “Cane brakes are common in some parts of Texas. They are tracts of land low and often marshy, overgrown with these long reeds. They are sometimes found as underbrush in woods and forests, and sometimes are not intermingled with trees, but form one thick growth, impenetrable when the cane is dry and hard. The frequent passage of men and horses keeps open a narrow path, not wide enough for two mustangs to pass with convenience. The reeds grow to the height of about 20 feet, and are so slender, that having no support directly from the path, they droop a little inward, and so meet and intermingle their tops, forming a complete covering overhead. The sight of a large tract, covered with so rank a growth of an annual plant, which rises to such a height, decays, and is renewed every twelve month, affords a striking impression of the fertility of the soil.

“Cane brakes often occur of great extent. Those of a league, indeed of several leagues are not uncommon. The largest is that which lines the banks of Caney Creek and is 70 miles in length, with scarcely a tree to be seen in the whole distance. The reeds are eaten by cattle and horses in the winter, and afford a valuable and inexhaustible resource of food in that season when the prairies yield little or none. At that time they are young and tender. When dry, they are generally burnt, to clear the ground.”

Mary Rabb, whose husband, John, was one of the Old 300, recorded many experiences years later for her children and grandchildren. She says that, “your Pa went to see about his folks, and as your Pa came back, he got lost and lay out in the Bernard bottom three days and nights without anything to eat and without water. Your Pa looked like he had been sick a long time when he got home, and he said his horse had liked to have died for the want of water and something to eat—as well as himself. He said there was nothing in the Bernard bottom. Your Pa said he had to hack his way through that bottom for him and his horse to get through. He said if it had not been for the big hack knife, they would have died and perhaps never been found.”

In 1831, Kentucky-born John Davis Bradburn, who was serving as a colonel in the Mexican Army, took command of the garrison at Anahuac, the small American community on Galveston Bay. This was a port of entry for American colonists that had been established as a Spanish fortress ten years before. Without reason, and not long after his arrival, Bradburn abolished the settlement of Liberty and confiscated the colonists’ land. He declared martial law and arrested several of them after they protested.

According to John Henry Brown, 160 angry colonists, including David Fitzgerald, attacked the garrison to rescue their friends. At the mouth of the Brazos River, another group on the way to Anahuac battled with Mexican troops at Velasco and defeated them. This was the beginning of the Texas Revolution.

Shortly after he took part in the battle of Anahuac, David Fitzgerald died. Three months later, his son-in-law, Eli Fenn, came looking for him because he and Sarah had heard nothing from her father in the ten years he had been in Texas. Eli liked the area, went back to Mississippi for his family; and they returned to Texas to live.

In February of 1833, after Eli had returned to Mississippi, three cases of the dread disease cholera had developed in an immigrant family who had recently arrived on a small schooner from the states. Although the settlers were told by two doctors that the disease was not contagious and should not be feared, five deaths were reported at the mouth of the Brazos by April 10th. The disease spread rapidly and would eventually spread into the interior of Mexico.

In May, as cholera continued to spread, the settlers had to deal with another calamity. Heavy rains had fallen since April, and both the Colorado and Brazos rivers were flooding. Here is an account from Creighton’s HISTORY OF BRAZORIA COUNTY:

“Day after day, great trees and islands of drift swirled down the quickening reddish waters of the Brazos. As the river neared bank level, creeks filled with backwater and crept slowly and silently onward, covering the whole country in one vast sheet of water. On the west side of the Brazos, the water reached the ‘Capitol Oaks’, located near the lower end of the business section of present day West Columbia.

“Around June 15, the flood crested. Mrs. Dilue Harris wrote then that the water extended from Buffalo Bayou to the Brazos. Planters built rafts and loaded their families, slaves, and goods on board to wait the recession of the flood. Slowly the river became less swift. Drift swirled toward the banks, indicating the worst was over. Green young trees standing in mud were uprooted by the falling water.

“Farther down the river, it still rose slowly until its crest moved out to sea. For two, and perhaps four, days, there was scarcely a change in the level of the massive backwater. Then, at long last, as the river level dropped, the entire country became a millrace as the backwater hurried to catch up with the falling Brazos. Behind was left a thick layer of silt, which emitted a sourish stench. Mosquitoes bred by the millions. By June 23, the flood passed, but cholera spread and became epidemic.”

William T. Austin wrote that he had come to Texas with his wife and one child three years before and was in the mercantile business in Brazoria. He said that the great overflow of 1833 damaged his goods, and what was left was taken to Washington to be disposed of. He said, “Directly after the overflow, the cholera made its appearance and scourged the whole lower Brazos country. My brother John Austin and all his family except his wife, and all my family but one daughter who is now living (1873) were taken off by this scourge. I buried both families and our slaves, 17 in all, in one week.”

William Morton had received a two-league grant on the east side of the Brazos, and exchanged one-fourth of a league with David Fitzgerald for that amount of the Fitzgerald League further down the river. Morton also received a labor on the west side where Richmond is now. Morton Street and Morton Cemetery are named for him. He was responsible for the first burial in the cemetery: A stranger named Gillespie came to Texas and was at the Morton home when he became ill and died. Morton, who was a brickmaker, buried him and made a brick monument for him. Mr. Wharton says, “Eight years later, William Morton died alone in the Brazos bottom and rests without a sepulcher.”

It seems that, during the flood of 1833, Morton was on his plantation a mile from home on the east side of the river and was carried away by the flood waters. Some sources say he was attempting to swim across the river from one side where his home was to the other side where his growing crops were. He was never found. [There is a rumor that William Morton used the flooded Brazos River to leave the area]

Eli Fenn arrived back in Texas with his family in June of 1833 just missing the two calamities just mentioned. They settled on the quarter league Fitzgerald had agreed to exchanged with Morton, and they farmed there. [This location is 3 miles below Richmond] At this time there was no more land available in Fort Bend County, so Mr. Fenn had his located in Grimes County. (Sowell) He also received a league of land in Madison County and a labor of land in Brown County. (Johnson, F.A.) Perhaps this is what he received later for serving in the Texas military.

In October of 1834, Nancy Morton, a resident of ‘the municipality of Austin’, filed a petition in the court of that jurisdiction as follows:

“That in the spring of 1833, her husband, William Morton, a resident of the municipality of Austin, abandoned his plantation and property in a state of mental alienation, and it is believed, left the Republic and went to the United States of the North where it is believed he still is and your petitioner has little hope of his speedy return, so that it becomes necessary for a curator or curators to be appointed by the Court to take charge of his property and to manage his affairs during his absence from the county.” (Abstract of Title, D. Fitzgerald League)

Mrs. Morton and Thomas Barnett were appointed Curators ‘of the vacant estate of William Morton, an absentee’. These papers and some of the others that we will mention were prepared by W. Barrett Travis, Attorney, later of Alamo fame.

Two months later, in December of 1834, John Fitzgerald filed a petition ‘to the Honorable David G. Burnet, Judge of the First Instance for the jurisdiction of Austin’, as follows, “The citizen John Fitzgerald represents to you that some time since, his father died in the jurisdiction leaving an estate of considerable value. He represents to you that previous to his death he made a verbal nuncupative will by which he made and constituted your petitioner his heir and constituted the citizen Randall Jones his Executor. He therefore prays you to cause Alexander McCoy, Miles M. Battell, William Little, John Jones, and John Morton who were witnesses to his said will to come before you and that you will take their testimony to the same and cause the said last will to be perpetuated and that you will declare your petitioner the heir to the estate of his father, David Fitzgerald, and you will grant letters testamentary to the said Randall Jones as executor of said estate.” (Abstract)

The men mentioned appeared before Judge Burnet and testified that “David Fitzgerald told witness that he and his son had come to this country together, that they had made the property here, and that having given to his other children their portions, he intended the property of which he died possessed to go to his son John Fitzgerald.”

The judge ruled that ‘the said John Fitzgerald is the declared and accepted heir to the estate of his father.” W. Barrett Travis was a witness to this instrument.

The next day,Dec. 25, 1834, John Fitzgerald deeded to Nancy Morton “one-fourth of the league of land that was granted by the Mexican Government to David Fitzgerald….in compliance and conformity with a contract made by his father David Fitzgerald in his lifetime with William Morton.”

Jesse Thompson was one of the Old Three Hundred; his headright league was near Brazoria. Later, he came up to the Fort Settlement (Richmond) and purchased a plantation in the Knight & White League, on the east side of the river. His homestead was near where the lower line of the Isaacs League reaches the river.

The Eli Fenn family lived on the quarter of the Morton League that Eli’s father-in-law, David Fitzgerald, had received in the exchange with William Morton. He loaned the boat, which he had made and which he used to haul cotton down the river and supplies back up it, to Mr. Thompson for use as a ferry when he was not using it. In a few years, Eli and Sarah would move down to the Fitzgerald League.

Mr. Thompson’s desire to have land on the other side of the river brought him trouble. Mr. Wharton quotes from a letter he found that Thomas Borden wrote in 1835. It says, “A man by the name of Jesse Thompson did live on the opposite side of the river from my farm and my place is precisely in his way for he is compelled to come on my side of the river in a high tide of water. Ever since the great overflow of 1833, he has been trying to get this place, I having purchased it before.” A quarrel continued for months, and one day when these two happened to meet on the road, shots were fired by each of them, and Mr. Thompson was killed.

Thompson’s family continued to live on the place until it was sold to Swenson after the Revolution. Jesse had 4 daughters and 4 sons, and the town of Thompson’s would be named for one of his sons, as we shall see.

Evidently, just before events of the Texas Revolution reached Fort Bend County, more legal papers were drawn up. On Feb. 20, 1836, Nancy Morton petitioned the court to have her deceased husband’s property divided between herself and her four children—Louisiana, wife of Daniel Perry; Mary, wife of W.P. Huff; John V., and William P., a minor being represented by John Fitzgerald as guardian. This division was made and Louisiana Morton Perry received the quarter of a league granted by the Mexican government to David Fitzgerald and by John Fitzgerald to the curators of the estate of William Morton.(Abstract)

Through the ensuing years, the Fenn family, mainly John R. and his grandson, J.J.Jr. (Button), would acquire portions of this land as well as land in the adjoining Thomas Barnett League. At the present time, we are familiar with a portion of the quarter league as the location of One Oak Chase Subdivision.

Years later, descendants of Louisiana Morton Perry would dedicate a cemetery on this property and would specify that as well as Perry family members and Sarah (John R.’s mother), John R. and Rebecca would have resting places there. Sarah’s husband, Eli, would be buried closer to the river.

Unfortunately, the cemetery dedication specified that no grave markers were ever to be used. Although the fencing around the cemetery has deteriorated through the years, it was located and identified, in 2002, by a Fort Bend County historical group with the assistance of Liz Fenn Stamey, who lives nearby. This little cemetery is adjacent to property owned by Annetta Rubar and her family, and they allow access to it from their property. It is possible that this is where Chelsea and Makayla Hubbard’s ancestor, to be mentioned later, is buried. Their grandmother, Barbara, and other Hubbard family historians have searched diligently to find where she is buried.

At this time, the Texans were seeking independence from Mexico in what was called the Texas Revolution. In LONE STAR, Mr. Fehrenbach, describes some of the events of that time. Sam Houston had been appointed commander of all troops except those at San Antonio. When at Gonzales, on his way to aid the men at the Alamo (in San Antonio), he heard the news that the Alamo had fallen. Since this area was thinly settled and his men poorly supplied, he decided to fall back, cross the Colorado, and be closer to the more populated area of Texas where farms and ranches could provide supplies and reinforcements. The troops did not have much grain for their horses; and because of almost constant rain, the muddy prairies provided little grazing for them. Houston ordered that all the men, except himself and a small cavalry detachment, give up their horses. Some of the men, who had come on their own horses, chose to return home rather than give them up. It was very difficult for those who did stay to give up their horses; the muddy roads made travel very difficult.

Although the Colorado River was at flood stage, Houston’s troops managed to cross it. While they were camped at Beason’s Ford (Columbus), they were joined by more volunteers. General Sesma’s army, which was pursuing the Texans, arrived at the Colorado and camped above and across from them. Preparing to fight, both armies held these positions for five days. Although many of his men wanted to fight the Mexicans there, Houston did not want to fight a battle he was not certain he could win.

Then, Houston received orders to proceed to Harrisburg (Houston) to protect the government personnel who had fled there from Washington-on-the-Brazos, where they had just signed the Declaration of Independence. The Texans had also been defeated at Goliad, so Houston’s troops were now the only ones left. As stated, many of Houston’s men wanted to make a stand at the Colorado because they did not want the Mexicans to reach the most populated areas where the lives of many women and children would be threatened. Mr. Fehrenbach says that “Columns under Santa Anna, Ramirez y Sesma, Filisola, Amat, and Urrea began a massive sweep toward the Sabine. Their orders were to burn every town, plantation, farm, and dwelling in their path. The Anglo-Saxon presence was not to be conquered or cowed; it was to be erased.”

Regarding all of this, Mary Rabb wrote, “In February, 1836, we was all drove out of our houses with our little ones to suffer with cold and hunger. And little Lorenzy, not three months old when we started, died on the road.

“When the Mexicans was invading Texas, your Pa had been in the service all the time, but I was sick and your Pa got a furlow to come home for a while. But your Uncle Thomas Rabb was still with the army as they retreated on this way. And your Uncle Tommy would keep telling Old Sam Houston that he had better fight the Mexicans and not let them invade Texas any further, that it would be worse and worse for us. But Old Sam was afraid and would not fight, and when they got nearly to the Colorado, your uncle told old Sam he had better drive them back. But he still let them come on, and when they got to the Colorado, your uncle told old Sam that if he let the Mexicans cross the river that he would lose half his men—that they would leave him and go to their families; and he had him to understand, that he, for one, would leave. Old Sam told your uncle that the Colorado would run with blood before they would cross; and your uncle said before daylight next morning the Mexicans was crossing the river. And your Uncle Tommy got on his horse and went to his family to move them on before the army. They lived at Egypt, near the Colorado. We always called the invading of Texas the runaway trip. Your Uncle Tommy’s wife only lived one day after they got home. There were many births and deaths on that road while we was running from the Mexicans.”

Houston studied his maps and ordered his men to retreat. They complained, with some of them feeling that Houston would retreat all the way to the Louisiana border and seek aid from United States troops in that area. Camp was made at San Felipe. The next morning, there were two captains who refused to continue retreating. To these two—Mosely Baker and Wiley Martin, Houston gave special orders. Baker’s 120 men would defend positions along the Brazos at San Felipe. And Martin’s 100, one of whom was Eli Fenn, would defend the crossings in the Fort Bend area. Mr. Fehrenbach says that “as the columns of women and children clogged the frightful roads and the struggling, sodden stream of pitiful humanity poured past Houston’s encampment at San Felipe, watching it, Mosely Baker broke down and cried.” Baker’s men kept the Mexicans from crossing the river at San Felipe; then he ordered the town burned.

The Mexicans proceeded down the river. There were several crossings in the Fort Bend area, as we shall see; Martin and his men were unable to defend them all. Santa Anna and his troops managed to cross the river. Martin, still refusing to serve under Houston, was given the assignment of taking charge of the refugees who were fleeing eastward ahead of the Mexicans.

Santa Anna’s officers kept diaries which show that they were not very familiar with the locations of the places whose names they knew. Almonte, who was with Santa Anna, wrote, “At 5:00 a.m., we left San Felipe. At half past 12 we arrived at Coll’s (Cole’s {Independence}) farm 6 ½ leagues from San Felipe. Three Americans were seen who took the road to Marion or Orizimbo, Old Fort, and leading to Thompson’s Ferry. We found at the farm a family from Lavaca who came by way of the Brazos. We sent the husband to reconnoiter at Marion, that is, the ferry.” (Actually, they sent him to give false information to the Texans and promised to pay him but never did.) Mr. Wharton says, “It is readily seen that Colonel Almonte confused Marion, (Columbia, just above Brazoria) with Thompson’s Ferry in the Bend, and Old Fort. He seemed to think all these were the same place. Almonte later mentioned capturing a Negro and having him show him where he had crossed. They crossed a little below the principal crossing place. He said that the cavalry arrived at ‘Marion’ and took possession of the houses. This reference to Marion means the houses in the Bend. They had captured the Jesse Thompson Ferry.”

As stated, there was confusion in 1836 about locations and events. Several history books perpetuate the confusion. Following, will be John R. Fenn’s account of the events of 1836 in the Fort Bend Area—he was there. There will also be accounts taken from other works. John says:

“We lived on the Brazos River, three miles below where Richmond now stands, in Fort Bend County. About the 7th or 8th of April, in 1836, we heard Santa Anna was within nine miles of us; and as my father, Eli, was away from home in Captain Wiley Martin’s Company stationed on the west side of the Brazos River, at Tom Borden’s place, two miles above Richmond, mother and I, thinking it unsafe to remain home, took two Negroes and went two miles up the river to Morton’s place, which was opposite Richmond, now the county seat of Fort Bend County.

“Captain Martin, hearing the Mexicans were so near, sent out Gil Kuykendall, John Shipman, and …Barksdale as spies to find out where the Mexican army was camped. They had ridden about sixteen or seventeen miles above Borden’s on the west side of the river, when John Shipman, who was on a large, fine black horse, raised up in the saddle to look as far down the road as possible, to his astonishment, he saw several Mexicans with Gen. Sesma coming towards him. The Texians turned, broke into a run, and were chased about seven or eight miles when the Mexicans’ horses gave out and they had to go back.

“Shipman and his two companions returned and reported to Capt. Martin, who then crossed the river with his company. They were followed the next day by Santa Anna’s army.

“Just here I will mention a mistake in history which says Santa Anna crossed this division of his army at Richmond. This is an error as they crossed at Thompson’s ferry, about four miles above Richmond. The boat they crossed in, my father made to use at this place.” (This was the ‘ferry’.)

“After all the white people who had gathered together for safety had crossed to the east side, they bored holes in the boat to sink it, but they were too small; it did not fill fast enough, and the Mexicans swam in and got it and patched it up and crossed their army in it.”

It is very interesting to note that Jose E. de la Pena, in his book WITH SANTA ANNA IN TEXAS, describes a similar incident as happening at Gonzales, Guadalupe Pass: “On the morning of the 5th a barge that had foundered between the two river passes was retrieved, fitted and taken to the upper pass.” This book gives very interesting descriptions of activities at Thompson’s, which he called ‘Old Fort’ (Richmond). However, he did not arrive there until the 17th after all of those we are mentioning were gone. Mr. de la Pena’s diary was not translated and published until 1975, and the introduction to his book states that in “none of the numerous folios in his military file is mention made of his participation in the Texas campaign or of his army career in 1836.” So, although his diary survived, his military records of this period did not. I, for one, question whether Mr. de la Pena was actually in Fort Bend County. Could it be possible that he used the contents of someone else’s notes in his diary? At the very least, he seems to have confused the Guadalupe and Colorado Rivers with the Brazos, as we shall see in other instances.

John Fenn continues, “Mother and all who were at Morton’s expected to leave on the morning of the 10th. We arose before day and were eating breakfast by candle light, when two old Negroes got in a quarrel; one of them belonged to the Mortons, the other to us. Joe Kuykendall made the Morton Negro mad, and he went to the river, crossing in a ‘canoe’ and started to go to Martin’s Company, as his master was a member of that company. He did not know they had already crossed the river.

“General Almonte, who was at the head of this division of Santa Anna’s Army, took the Negro prisoner and made him show him the canoe he crossed in, which the Negro did, and Almonte crossed about fifty of his men to the east side of the river and the remaining soldiers began firing on the west side.”

Here are five other descriptions of the same event”

Sowell’s HISTORY OF FORT BEND COUNTY: ‘After having a controversy with John, whom David Fitzgerald brought to Texas, Cain, who belonged to John Morton, left the place (Morton’s). He went to the river and secured the small boat that was used for crossing the river, and crossing to the west side, tied it up and started across the bend toward Borden’s. He came upon the ambushed men of Almonte, who spoke to him in English: ‘Good morning, Uncle.’ Cain recognized him as a Mexican and said, ‘I got no good mawnin’ for ye, suh,’ and proceeded on his way. After another attempt to speak with Cain, Almonte whistled and about a dozen soldiers arose from the grass, aiming their muskets at him. Cain surrendered, was taken into custody, and made to conduct them to the boat in which he had crossed. They managed to make several trips and land about 50 soldiers on the east bank before being discovered by the people at Morton’s, who fled in terror.”

Col. Almonte’s account, as quoted in Wharton’s HISTORY OF FORT BEND COUNTY: “Monday, April 11—Still in ambush, quarter of a league from Thompson’s (he called it Marion). A negro passed at a short distance and was taken. He conducted us to a place he had crossed, and having obtained a canoe, we crossed a little below the principal crossing place.”

The 1996 HANDBOOK OF TEXAS: “We spied a black ferryman on the east bank of the Brazos. Col. Almonte hailed the ferryman. Probably thinking that this was a countryman who had been left behind during the retreat, the ferryman poled the ferry across to the west bank. Santa Anna and his staff, who had been hiding in nearby bushes, sprang out and captured the ferry.”

Tolbert’s THE DAY OF SAN JACINTO says, “From the west bank of the river, the Mexican advance guard could see a Negro ferryman on the opposite shore. Santa Anna and some of his staff hid themselves in brush, and Almonte called in his good English to lure the Negro to the west bank. It was said that when the ferryman was on the shore, Santa Anna himself leaped from ambush and wrestled with the Negro. At about the same time, Wiley Martin realized that he didn’t have enough men to defend the crossings around Fort Bend, and he fell back from the river.”

Wallingford’s HISTORY OF FORT BEND COUNTY says, “The Mexicans discovered and commandeered a small rowboat left hidden in the grasses on the west bank.”

Now, after reading six descriptions of the same incident, answer these questions:

Was Cain a ‘ferryman’?

Was he ‘summoned’ across the river?

What craft did he use to cross the river?

Do you think that Cain ‘mistook’ a Mexican colonel in uniform for one of his own countrymen?

The Mexicans were now crossing the river at Thompson’s Ferry and at Morton’s. John Fenn continues, “Kuykendall saw them from the house, saying, ‘Ladies, there is Houston’s army; let’s go down and take a look at them’.

“His wife and one or two others went. When they got opposite there, Joe Kuykendall turned suddenly saying, ‘It is the Mexican Army.’

“At that moment 12 or 15 Mexicans who were hid under the bank of the river, rose up and fired at them. Kuykendall was a cripple and could not run; he laid still and the ladies all ran. His wife ran in the house and opened a trunk and took $1000 in paper money and $400 in silver and ran out of the house into the woods. The silver was in a bag, and as she ran through the woods she threw the bag of money in a forked tree and ran off and left it. Of course that was the last she ever saw of it. There were six ladies, Mesdames, Joe, Abe, and Gill Kuykendall, Miss Jane Kuykendall, Mrs. Jeans, and mother.

“My father, seeing the women running in every direction and the Mexicans shooting at them, ran across an old field that surrounded the house and saw a Mexican sitting on the fence, shot at him and killed him and drew the attention of the Mexicans to him, which caused all of the others to run.”

Mr. Sowell describes this incident: “Eli Fenn, being uneasy about his family, left the ferry, although ordered not to do so by Captain Martin, and hurried to Morton’s, but arrived there just as all the people had scattered away from the house. Seeing he would be cut off before he could reach his people, he stopped for a moment to consider and discovered a Mexican on the yard fence, and hastily bringing his rifle to his shoulder, shot him off and then turned and ran back up the river, pursued and fired at by the Mexicans who had discovered his presence by the report of his rifle. His flight was somewhat impeded from the fact that he had on a long-tailed linen coat, in the pockets of which was several bars of lead which flapped him about the hips as he ran. This episode, no doubt, aided in the escape of the women, by drawing the attention of the Mexicans from them to Fenn. Before he got back to the ferry, he met some of Martin’s men coming down to see what the firing meant, and learning the fact that the Mexicans were crossing there, hurried back and reported, and Captain Martin perceiving that he would be flanked if he held his position any longer at the ferry, retired and joined Gen. Houston above.”

John continues, “The ladies, by this time, had all gotten to the woods. Joe Kuykendall was taken prisoner. Myself and Negro boy, Jack, went to drive up some horses. We did not get back until about 7:30 or 8:00 o’clock. We rode into the lines and were taken prisoners.”

Before we hear John’s version of his captivity, let’s see what Mr. de la Pena has to say. But, he says this happened as they were crossing the ‘Colorado’ and: “I met two young boys of 10 or 12 who lived in one of the dwellings on the banks of the river and who, having gone hunting, returned to find their parents gone. Looking for help where they knew people lived, they ran into the troops. They assured me that several families had fled. Through the compassion that is naturally aroused by the sad plight of orphans, I asked to take one of them and that one of my companions should take the other, but we were told that they were to leave the next day with a Frenchman, who had already taken charge of them the day before and who had himself escaped from the enemy.”

John says, “I remained a prisoner until evening, when Gen. Almonte told me he was going with his men to Thompson’s place and capture Capt. Martin’s Company, and he would leave me and the Negro boy there until he came back the next morning; and for me to go and find my mother and bring her in, and she should have her things restored to her. He would make the soldiers give them to her as Kuykendall said she was one of the ‘Old Three Hundred.’ He made me give my word of honor I would be there the next morning when he came back. I slept that night in the river bottom with Jack. Next morning before daylight we went with a Negro woman who had heard from two men, of my mother and some of the ladies escaping safely, and advised me to go with her to them. While we were talking the Mexicans returned, and the main body of the army appeared on the opposite side of the river. In a few minutes the ‘Yellowstone’, a steamer that brought Houston’s army across the river at Groce’s Retreat, appeared around a bend in the river, and the Mexicans made a charge and tried to rope her.”

Again, interestingly, Mr. de la Pena has a different version. He says that this happened at San Felipe. He says that the Mexican soldiers were ‘dumb founded’ and ‘surprised’ because they had never seen a steamboat. They fired a shot at it from their eight-pounder. He says that Gen. Sesma was criticized because ‘the steamboat had remained anchored for several hours to take on wood at a short distance upriver from his camp; he had not known it.’ He doesn’t mention what we shall learn in a moment from the HANDBOOK OF TEXAS.

Mr. de la Pena, on page 109, says that it (the steamboat), no doubt, “could have been taken by placing strong obstacles in the river that would have prevented its passage; this could have been done with small effort by throwing from both banks of the river thick trees held together with chains.”

This statement by Mr. de la Pena is an example of why I question whether he was actually in the Fort Bend area. I feel he may have been confusing the Brazos and the Guadalupe rivers. Have you seen these two rivers? Do you think that it would take ‘small effort’ to stop the passage of a steamboat on the Brazos by throwing thick trees held together with chains across it?

Now, let’s see what the HANDBOOK OF TEXAS says about the Yellowstone on that occasion: “On a trip in February, 1836, the vessel, under Captain J.E. Ross, went up the Brazos River as far as San Felipe. On March 31 it was half loaded with cotton and was tied up at Groce’s landing, when Sam Houston and the Texas Army arrived. Houston impressed the ship to transport the army across the Brazos.” The Texas government was later billed for this transportation as well as 14 days’ detention. “The Yellowstone then proceeded downstream and picked up refugees of the Runaway Scrape and ran the Mexican gauntlet at Fort Bend despite Mexican shots and efforts to lasso the ship.”

So, the account of Mr. de la Pena, whose military records did not survive, does not agree with the H.O.T. information which was obtained from ‘Ship Registers and Enrollments of New Orleans, LA, 1831-1840’; but John Fenn’s account does.

Back to John: “I kept my word to await the return of the Mexican officer, and as the excitement was going on aboard and about the boat, I thought it a good time to leave. So I ran to the woods, being shot at a great many times by the Mexicans. The leaves shot from the trees fell all around me, but I kept going. At the time of my escape from the Mexicans, I was not quite twelve years old. After I got to the woods, I passed my home and went 10 or 15 miles, where I found several families, William Little, Joe Johnson, and several others.

“About an hour, I suppose, after I arrived here, Joe Kuykendall came with the Negroes. Mr. Kuykendall said he had promised the Mexicans if they would let him go and look for his wife he would come back and give them $1000 and 100 four-year-old beeves. They gave him a pass to go and return. About this, S.B. Oates says that Mr. Kuykendall “stated that he had been taken prisoner by some Mexicans while eating his dinner in his own house; that he was taken before Santa Anna, who received him kindly, and then gave him his liberty, telling him to go and hunt up Gen. Houston and tell him that he, Santa Anna, was tired of hunting after him and his army like so many Indians in the woods, but that if he would come out of his hiding place, he would give him a fight in the open prairie.”

John continues: “We traveled together all night; got to Harrisburg at daylight. Traveled on that day and came to Lynchburg. Here I found my mother and some of the others. They had walked for miles through mud and water and a keen ‘norther’ blowing. Some of them, men, women and children, without shoes and half clothed; they had to leave just as they were to save their lives.

“We all struck out east together, crossing the San Jacinto River and kept going on as fast as we could. ‘Uncle Joe’ kept saying over and over ‘if the Mexicans catch us they will kill us sure.’ We came to one of the bayous that empty into the bay. We had no rafts or boats to cross in, so we attempted wading across the sandbar at the mouth of the bayou. A big wave would come along, knock us over; we would get up and start again.

“Notwithstanding all our hardships, we made another attempt to move forward. We at last reached the Neches River where my father joined us. Gen. Gaines, commanding United States troops near San Augustine, had given the Indians a scare, and they had all left that part of the country.

“In consequence, Capt. Martin had turned all of his men loose in Eastern Texas to go and hunt up their families.”

About Capt. Martin, Mr. Tolbert says, “Old Wiley Martin, worn out from the hopeless job of trying to guard the Fort Bend crossings, was convinced that Houston wasn’t going to fight, and he didn’t want to go on serving under the General. Houston and Martin had once been good friends, and the General didn’t make an issue of Martin’s insubordination. He ‘ordered’ Wiley’s company to guard the crowd of refugees clinging to the army. The next day the civilians turned left at a fork in the road, while Houston turned right toward Harrisburg” and his subsequent victory over Santa Anna at San Jacinto.

However, Mr. Oates says that when Martin arrived at Houston’s camp after leaving the river crossing, he said, “General, I have brought but my sword; my company has disbanded. On hearing that you were retreating to Nacogdoches, they declared they would no longer bear arms, but would protect their families; and they have therefore all dispersed.”

John says that his “father took mother and I to Louisiana and left us. He returned to the army of the Texas Republic where he served until the autumn of 1836, when he procured a discharge and went after us.

“We arrived in the latter part of November at the Brazos, now a part of Fort Bend County, where I have lived ever since.” J.R. Fenn.

When the settlers came back to their homes, they discovered that their belongings were stolen and their houses burned. Supplies valued at $300 had been stolen from Eli Fenn, and it cost him 2/3 of a league of land to pay off the debt to White & Knight in Columbia, according to Mr. Sowell.

Possibly, this land, or part of it, was the quarter of the Morton league where Eli and his family lived. Because of this, and because their home had been destroyed, they moved down the river to the Fitzgerald League.

After the victory by the Texans at San Jacinto, Columbia (now West Columbia) served as the first capital of the Republic of Texas. After three months, it was moved to Houston and was there until 1840 when it was moved to Austin.

Among the signers of a petition of Fort Bend, Texas, to become a county, dated May 14, 1837, was Eli Fenn. This document is on display at the Fort Bend Museum, Richmond, Texas.

The Texas Congress awarded all married men who had served in the military a league and labor of land. Eli was granted patent #57 for his service in the Texas Military: “This is to certify that Eli Fenn has appeared before us, the Board of Land Commissioners for the County of Fort Bend and proved according to law that he served in this Republic and that he is a married man and entitled to one league and one labor of land upon the condition of paying a total of one dollar and twenty cents for each labor of pasture land, two dollars and 50 cents for each labor of arable land, and three dollars and fifty cents for each labor of irrigable land which may be contained in the survey secured to him by this certificate. Given under our hands this the 8 January 1838; Wm. F. Pool, clerk; R. Jones, President; Daniel Perry; …Thompson.”

In the next month, February, 1838, Eli served on the first grand jury of Fort Bend County.

On May 12, 1838, John Fitzgerald, for the some of $100, deeded to his sister, Sarah, and her husband, Eli, “a certain tract of land known as the North West quarter of the league of land granted by the Mexican government to David Fitzgerald. The said Bargain and Sale is made for and in consideration of the sum above mentioned and also to fulfill a certain bond and obligation made by the said John Fitzgerald to the said Sarah C. Fenn which bond and obligation being now fulfilled is hereby forever cancelled and made void.” (Abstract) [John Fitzgerald is the brother of Sarah Catherin Fenn]

On February 4, 1839, John Fitzgerald, brother-in-law of Eli Fenn, was elected justice of the peace of the Eighth District of Harrisburg County.

In 1840, Eli Fenn died. The cause of his death at the age of 46 is not known. John Fenn, who was sixteen at the time of his father’s death, said he buried his father about 400 yards below where the bridge of the Santa Fe Railroad spans the Brazos; and some think the remains were carried away by the great floods, but John did not think so. The exact spot is lost.

The master-planned community of Sienna Plantation now being developed (late 1990s) contains 800 acres along the river (outside the levee that protects the subdivisions) that are devoted to recreation, open space, and nature. Perhaps this area includes Eli’s resting place.

In the Republic of Texas, Fort County, on11-23-1840, Sarah C. Fenn, widow of Eli, sold 625 acres of land to Robert G. Waters for $3125. The description states: “Beginning on the east bank of the Brazos River at the southwest corner of the northwest quarter of a League of land granted originally to David Fitzgerald” and continues with distances given in varras and degrees, and markings of X or W placed on trees—tooth ache tree, hackberry 8 inches in diameter, pecan 3 feet in diameter—crossing Oyster Creek twice, stakes in the ground, more varras and degrees, a 6-inch wild china tree, then back to a stake on the river “thence down the river with the meandering thereof to the place of beginning.”

During the ten years after the Texans won their independence from Mexico, Mexican forces crossed the Rio Grande to attack settlements in Texas. In DARE-DEVILS ALL; TEXAS MIER EXPEDITION, Joseph M. Nance, tells of events of that time. After one of these raids in l842, Texas President Sam Houston called on volunteers to retaliate. In November, Brigadier General Alexander Somervell left San Antonio with a 759 man army. By the time they reached Laredo, the Mexicans had gone back across the river. The Texans had been ordered not to cross into Mexico.

However, after capturing Laredo, some of the volunteers plundered the town while others returned home. Somervell’s troops, now fewer in number, marched down the Texas ide of the Rio Grande until they were across from Guerrero, where he had them cross the river to obtain supplies. Crossing back into Texas, he ordered his troops to return to Gonzales to be disbanded. Many of his men wanted to fight the Mexican army and many wanted to plunder Mexican towns. Discipline was a problem; the troops needed horses, food, clothing, and ammunition.

Moses Austin Bryan later reported that 300 men mutinied and remained on the Rio Grande. When General Somervell ordered a march home, five captains refused. One of them, Captain Fisher, said he would take his men down the river far enough to procure horses and provisions. He thought they would reach home as soon as those who marched with Somervell.

John Fenn, age 18, asked Lt. John Shipman, “John, which way shall we go?” Shipman replied that they were good soldiers and should obey orders. But then he, Shipman, decided to go into Mexico with his captain. Fenn was going to go along, but Robert Herndon took hold of his bridle and said, “Come John, you are young, go back with me”, and John did. William Sullivan and a man named Woodson also came back.

About this, John Fenn said, “I went to defend the Lone Star whenever she called for volunteers; always furnished myself with horse, gun, etc, as all Texians had to do when they went to defend their country. I went to San Antonio in the spring of 1842, and again in the autumn of the same year with Gen. Somervell, as a member of Capt. William Ryon’s Company, when the Mexicans under Woll were again invading Texas.”

Among those who went into Mexico was John’s uncle, John Fitzgerald. The Texans attacked the Mexicans at the city of Mier and were defeated. After being imprisoned, some escaped. When recaptured, they participated in the ‘death lottery’—the drawing of beans from a jar, with one black bean for each 10 white ones. These who drew black ones were executed. Evidently, John Fitzgerald and John Shipman drew white ones. Shipman would die in a Mexican hospital.

While imprisoned at Perote Castle, some managed to escape on Aug. 25, 1843; one of those was Fitzgerald. They reached the top of the wall around their compound by climbing on a companion’s shoulders, then lowering themselves to the ground with a rope. They found a paper mill where they were given shelter for three weeks. They were then taken to the residence of the English Minister. There they were fed and protected for two days, given $20 each, and driven out of Mexico City in a carriage at night. They were placed on the road to an English silver mine, and when challenged, said they were miners and showed the passports the English Minister had given them. At the mining town, they were helped with plans to get to the coast. Deciding to go to Tampico, then on to New Orleans, John Fitzgerald reached Texas six months later.

Of those who did not escape from prison, many died and others were liberated over the next two years.

Fitzgerald resumed his life in Texas.

Previously, on February 4, 1839, John Fitzgerald was elected justice of the peace of the Eighth District of Harrisburg County.

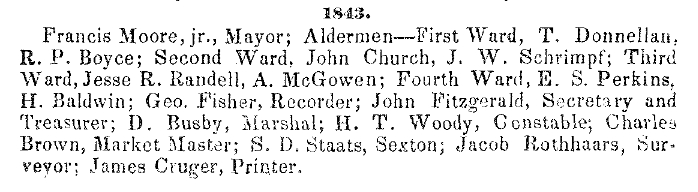

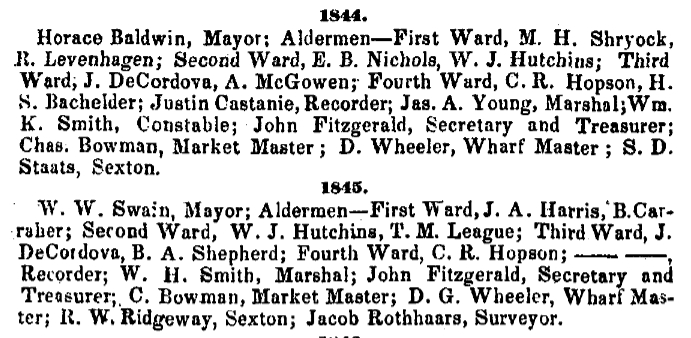

On 4-27-1844, he was elected sheriff of Harris County. He later

served as secretary pro-tempore of the Houston City Council. In January, 1846, he was elected by the City

Council to be City Treasurer and Secretary.

The following is from the City of Houston Directory of 1866.

A sister-in-law of Sarah Fenn and John Fitzgerald, Catherine, a resident of Washington Parish, Louisiana, sent her attorney to Texas in search of any inheritance she might be due from the estate of her father-in-law, David. She was the widow of Sarah and John’s brother, William. A legal instrument recorded on Nov. 11, 1845, says that the attorney received full satisfaction from John, and “The whole business having been amicably settled by myself and John Fitzgerald, he is from this day forever acquitted from us in said estate of David Fitzgerald, deceased.”

Sarah was 43 when her husband, Eli, died, and she lived another twenty years. The chapter, ‘Mrs Eli Fenn’ in PIONEER WOMEN IN TEXAS, BY Annie D. Pickrell, says, “Four years after the victory at San Jacinto, Sarah was left a widow in the wilderness, her son, John, her only companion: But she had another son, Jesse, who was five years old at the time of the Runaway Scrape, although he was not mentioned by his brother, John. Jesse is mentioned in Mr. Sowell’s HISTORY OF F.B.C. as well in census records. Jesse was about nine years old at the time Ms. Pickrell says Sarah had only her son John as a companion. We will see later perhaps why Jesse was not mentioned by John or by his daughter, May Fenn McKeever, who gave Ms. Pickrell the information she used in her book.

Ms. Pickrell also does not mention that Sarah had a second marriage—to Collin Cox. But, Mr. Wharton mentions it and says that Cox had a quarrel with a neighbor, Waters, about some land. Waters went to Cox’s home and murdered him in Sarah’s presence. This was reported in the Houston Telegraph.

Sarah was now widowed for the second time. Ms Pickrell reports that “With her first pangs of grief sustained” (and, hopefully, the second, as well), “Sarah remembered that she had studied both botany and chemistry.” This must have been in Mississippi where she married at the age of 20. She had a “real knowledge of plants and their medicinal value. She grew poppies in her garden, distilled them, and made valuable medicines. She found herself called upon to visit the sick, to diagnose difficult cases, to serve, in short, as any family physician would serve under the same conditions.”

Sarah would not be able to do this today, because growing this variety of poppy, from which opium is produced, is illegal now. Opium is a powerful drug that causes sleep and eases pain. It is a narcotic and is used illegally to stimulate and intoxicate.

Ms. Pickrell also reports about May’s grandmother that “she finally stood the medical examinations and was admitted formally to the practice.” It is quite certain that Sarah did administer to the sick, but there is no documentation among the abundance of old family papers that we have that she officially became a doctor.

In 1845, Rebecca Williams, future wife of John R. Fenn, came to Texas with her family. She was ten years old. Their first year was spent in the old homestead of Moses Shipman. The logs and boards of the house were all made by hand and joined together with wooden pins as there were no iron bolts or nails available. They used water from creeks and ponds. The home of ‘Judge Senior’ would later be at this location.

In l852, Rebecca Williams and John R. Fenn, who lived on neighboring plantations in Fort Bend County, were married. He was 28; she was 17. As a young man, John R. liked to hunt and was a good shot. Mr. Sowell tells some stories about John that were probably given to him by John’s son, Otis: “On one occasion, the dogs treed something near the house, and thinking it a coon, John and John N. Norris went to the place without a gun, thinking to chunk the ‘varmint’ out and let the dogs have a fight with him. It proved to be a half-grown panther; and when the two men approached the tree, it jumped out and ran between Mr. Fenn’s legs, nearly upsetting him, but was caught by the dogs and killed by Norris with a knife.

“On another occasion, Mr. Fenn shot a large bear and it fell near the bank of the river, where the bluff was very high, and out of sport, he sprang from his horse, mounted the bear and drove his spurs to him. Bruin raised his head, gave a loud sniff, and was about to make a spring forward, his nose being nearly over the bluff, when Mr. Fenn quickly drew a pistol and shot him in the head. If the bear had made the leap, he would have gone over the bank and carried the hunter with him on his back.”

According to Mr. Johnson in A HISTORY OF TEXAS AND TEXANS, Mr. Fenn owned many acres of land in the Brazos Valley, especially Fort Bend County. He had large herds of cattle, and he raised cotton and cane with the help of slave labor.

At the beginning of 1859, John R. was almost 35 and his brother Jesse was almost 28. (Some material says that Jesse was the oldest, but Mr. Sowell, p. 92, says that, in 1836, Jesse was five and John was twelve.) Their mother, Sarah, widow of Eli Fenn and Collin Cox, was about 62. She may have been ill, as she died the following year, 1860. In January, 1859, she executed a legal document which was not a will but a Deed of Gift. It listed 13 slaves, 500 acres of land, and 130 cattle and said, “And whereas the said Sarah C. Cox has two sons John R. and Jesse T. Fenn, citizens of said county, and whereas the conduct and illtreatment on divers occasions of my said son Jesse T. are of such a character that I am unwilling that the said Jesse shall have now or even at my death any of my property.” She deeded the property described to John R., but she had not mentioned property in Brown County.

Jesse married Irene Trotter of Houston. Their six children were James, William Jesse (father of Thadeus), Edward Lawrence, Frank Robert, Ada, and Sarah Katheryn. Jesse wrote his will in 1863—it is not dated, but he said he was 32 at the time. He died in 1873 (will was filed 4-25-1873) at about the age of 42. In his will, he asked that all his lawful debts be paid, and he desired that his estate be managed and controlled by “my brother John R. Fenn” as executor. He also expressed the desire that his children be “as well educated as the means left will afford and that whatever property may be left be equally divided between my children when the youngest becomes of age.”

On 3 March 1874, J. R. Fenn solemnly swore that he would perform the duties of executor of the last will of Jesse T. Fenn deceased. Acting in this capacity, John R. sold, in 1885, to J.W. Mitchell of Harris County, Texas, “the undivided 44 acres of land belonging to the estate of J.T. Fenn out of the Eli Fenn labor in Brown County.”

During the four years of the Civil War, the 400 mile Texas coastline had to be defended against Union attack. Forts were built of live oak and surrounded by earth works at Velasco and Quintana. John R. Fenn did home guard service with Bates’ command near the mouth of the Brazos.

John R.’s wife, Rebecca, had two brothers who fought in the Civil War, and both of them died in the Federal prisoner-of-war camp at Fort Butler in Illinois. Their names were Joseph Smith Williams and Johnson Coddington Williams. Rebecca would name one of her sons Joseph Johnson Fenn, and the name would be used for the next two generations as well.

When Jonathan Waters died in Fort Bend County, according to Mr. Sowell, his wife inherited his property; she sold it to Thomas Pierce. In 1872, Pierce sold it to T.W. House. Mr. House anticipated having a partnership with John R. Fenn, but that did not happen. Some people told House that he would lose money because he ‘had an elephant on his hands’. They advised him to sell out. Instead, he kept the property, improved it, and hired Mr. Fenn to manage the plantation for him. This was done successfully, proving that Mr. House did not have an elephant on hands. Under Fenn’s management, the plantation gradually increased until it encompassed thousands of acres of fine Brazos bottom land.

In an affidavit for an oil company, years later, J.J. Fenn Jr. (Button) said, “For a number of years my grandfather worked for Mr. House on his plantation. Ninety percent of the land was in cultivation; Mr. House raised mostly cotton, corn and sugar cane on the land. He had a large sugar mill and made sugar each year. Mr. House always kept a large number of work animals, and he always kept his fences up.”

In 1876, John R. Fenn bought 75 acres of land in the David Fitzgerald League from Jane H. Perry, a descendant of William Morton.

The little piece of land where we (Joe, Mona & kids) lived for 14 years is part of the Thomas Barnett League; and at one time, it was the property of James Shipman. As the following documents will show, it was purchased in 1885 by John R. Fenn. In 1931, Mr. Button, John R.’s grandson acquired it. This area has now been subdivided, [Silverdge Subdivision] and the Reyes family owns a portion of this little place, including the house that was built for us in 1960 by Frank Haisler. The remains of an old sugar mill are still there—near where Joe built his cattle pens and just in front of the little bridge that crossed the creek.

One of the documents mentioned is an Order of Sale, No. 3188, dated Nov. 9, 1882, W. P. Rather et als, v. E. M. Shipman, et als. (This instrument refers to tracts of land in Fort Bend, Karnes, Bexar, and Taylor Counties. We are concerned with that in Fort Bend. Two of the two dozen or so people named are Mary V. and James Fenn, son of Jesse T.) The Court determined that “the lands sought to be partitioned are not susceptible of a fair and equitable division among those entitled thereto, & said commissioners advise a sale of said lands with the proceeds thereof divided among the heirs of James R. Shipman, deceased.”