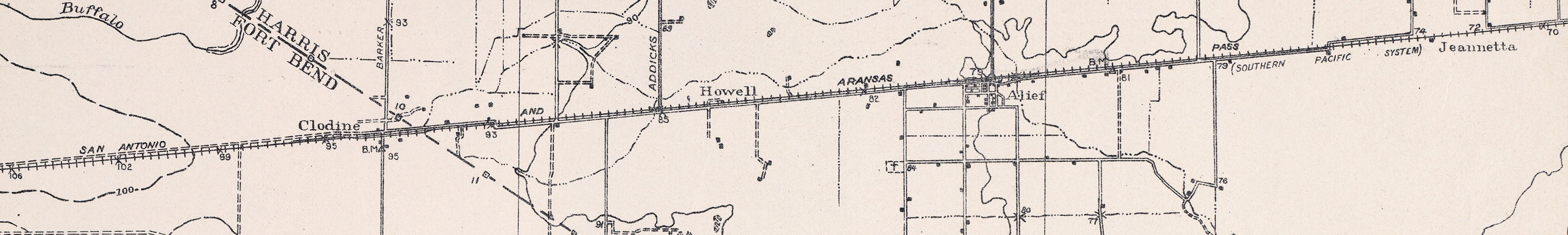

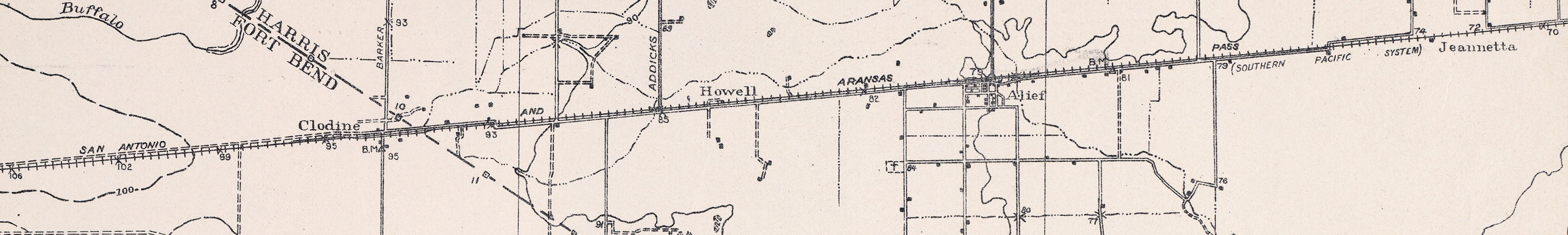

San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railroad

There was a road that ran beside the railroad that was not named. Today this road is known as Westheimer or FM 1093.

The towns in Fort Bend County on this railroad are Simonton, Fulsher, Flewellen, Gaston and Clodine. The town that wanted the railroad but did not get it, and therefore disappeared was Pittsville.

|

1884 |

SA&AP |

The

San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railway Company was chartered on August 28, 1884,

to connect San Antonio with Aransas Bay, a distance of 135 miles |

|

1888 |

SA&AP |

During

the years 1887 and 1888 the SA&AP constructed 176 miles between Kenedy

and Houston. It takes a more northerly path through Fort Bend County than the

GH&SA Sunset Route, and passes through Fulshear and Simonton. |

|

1892 |

SA&AP |

The

SA&AP is purchased outright by the SP. By this time, the SA&SP was

operating 688 miles of main track, and owned fifty locomotives and 1,388

cars. |

|

1903 |

SA&AP |

The

Railroad Commission brought suit for forfeiture of the SA&AP charter in

order to compel the SP to divest itself of ownership. The SA&AP becomes

independent again. |

|

1925 |

SA&AP |

The

Interstate Commerce Commission authorized the SP to regain control of the

SA&AP, and the company was leased to the GH&SA (a SP subsidiary) for

operation |

The railroad right of way use today through Harris Couny is interesting. It is the railroad roadbed that runs parllel to, and just south of FM 1093, or Westheimer. The Westpark Toll Road is built on the right of way. After the Westpark curve of the Southwest Freeway the railroad ran parallel to and less than a block south of the Southwest Freeway to Fannin Street before it becoms invisable because of the progress of Houston.

Very soon, however, the sugar cane empires of Dunovant, Eldridge and other local planters crumbled. Competition from sugar imported in the form of molasses from Cuba, Hawaii, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico, as well as sugar domestically refined from the more economically produced sugar beet, increased rapidly in the early 1900s. Moreover, in 1910, responding to assertions of inhumane treatment, the Texas Legislature outlawed convict leasing, removing what had been a reliable source of temporary labor for the growers. Notwithstanding the assurances of the G.C.&S.F. Colonization Department, a devastating freeze in December 1911 decimated sugar cane production, resulting in the loss of about 50 percent of that year’s crop . There would be subsequent freezes as well. By the mid-1920s, the combined effect of competition, bad weather, and expensive labor had reduced cane production substantially and virtually halted the manufacture of sugar in the Cane Belt territory. The Lakeside Sugar refinery ceased operation after processing a small amount of the 1911 crop. It was dismantled in 1918 and shipped to Jamaica for reassembly by the purchaser. Captain Dunovant did not live to witness the decline of his beloved sugar industry, as a disagreement with Eldridge over the operation and management of the Cane Belt Road blossomed into a fatal meeting between the two on August 11, 1902. According to the Houston Post:

At 5:30 yesterday (Monday) evening Captain William Dunovant, one of the most prominent planters in Texas, was shot and fatally wounded b y W.T . Eldridge, Vice-President of the Cane Belt Railroad. . . . The tragedy occurred onboard Train Number 2 of the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railroad at Simonton, a small station east of Eagle Lake . . .After inspecting a sugar cane crop, Dunovant boarded the train at Simonton Switch. Eldridge, already aboard, “opened fire with a revolver” as soon as he saw Dunovant. Although one bullet later proved fatal, Eldridge was not willing to chance Dunovant’s escape. After exhausting the chambers of his weapon, Mr. Eldridge leaped forwarded and aimed a terrific blow at the captain’s head. A bystander parried the blow, but it fell with sufficient force to lacerate Captain Dunovant’s scalp. The latter then sank into the arms of the bystanders. . . .Both of the principals in the tragedy are well known throughout Texas and the causes which led up to the tragedy are familiar to the entire community. Differences which arose in the management of the Cane Belt Railroad, it is said, engendered a feud between Mr. Eldridge and Captain Dunovant.

The Eagle Lake community was shocked but not surprised by the murder. The local press commented that Dunovant was “peculiar in some respects, being very outspoken in his opinions of men and measures . At a habeus corpus hearing was held to consider bond for Eldridge after he was charged with Dunovant’s murder , the judge fixed bail at $25,000 , stating that “There is no doubt in my mind but the deceased made threats.” Testimony from the trial indicated that Dunovant had publicly threatened to kill Eldridge on several occasions, asserting him to be a liar, a cheat , and a “dog-faced s.o.b.” Dunovant believed that Eldridge had defrauded him of his share of their joint interests in the Cane Belt line and in their farming partnership. Ensuing even its demonstrated that there also were deep hard feelings between supporters of Dunovant and Eldridge. Within weeks the first attempt at revenge occurred. On October 4, 1902 at 10:30 p. m., a shotgun was fired at Eldridge as he climbed the steps to his front porch, but the blast missed its intended target . W. T. Cobb was promptly arrested and charged with assault with intent to murder. Cobb was indicted on March 10, 1903, and his case went to trial that September, before Eldridge’s trial for the Dunovant murder. The press reported that “interest in the case has been unabated, and the testimony . . . has been to a certain extent sensational.” On September 2 , 1903 a jury found Cobb not guilty.

Counsel for Eldridge succeeded in delaying his client’s trial throughout 1903 and for part of 1904. The effort bought time, but not peace. On June 6, 1904 a second and more serious attempt was made on Eldridge’s life by W. E. Calhoun, one of Dunovant’s brothers in-law. By this time the Houston Post’s 1902 assessment of the matter as a “feud of long-standing” appeared prophetic. The local press reported that Eldridge was “shot from ambush” out of a second-story window with a 30.30 Winchester rifle; the slug passed through his right lung, above his heart and through his left hand, and finally lodged in a six- inch wooden sill under the Southern Pacific depot. Eldridge recovered from his wounds, and on July 4, 1904 announced that he would retire from his position as vice -president and general manager of the Cane Belt and move to Houston. On July 6, 1904 Calhoun was released from custody, with the press reporting that although he was ar rested “at or on the stairway leading to the building from which the shot was fired . . . no witnesses appeaed against him . ” The case was referred to a grand jury. Eldridge was finally brought to trial for Dunovant’s murder in November 1904 and was acquitted. In March 1905 a Colorado County grand jury failed to return an indictment against Calhoun for the July 1904 attempt on Eldridge’s life and that case was dismissed. Within weeks, Eldridge again took matters into his own hands and fatally shot Calhoun upon discovering him to be a fellow passenger on board a train bound from San Antonio to Houston. Eldridge, who boarded the train first, fired three shots before Calhoun could unholster the pistol he was carrying. Eldridge’s trial for the shooting of Calhoun began in Bellville on January 16, 1906 amid a fevered pitch of community emotion. The district judge ordered that all persons entering the court room be searched for weapons. A motion for continuance was granted, and the trial was reset to January 1907, when Eldridge was again acquitted. Eldridge pled self-defense at both trials. The juries were so persuaded, but he obviously had revenge on his mind. A cryptic epitaph on Dunovant’s tombstone reading “I will be avenged” notes that the enmity carried to the grave.

The San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railway Company was chartered on August 28, 1884, to connect San Antonio with Aransas Bay, a distance of 135 miles. The capital stock was $1,000,000, and the principal office was in San Antonio. Members of the first board of directors were Augustus Belknap, William H. Maverick, Edward Stevenson, Edward Katula, Daniel Sullivan, A. J. Lockwood, George H. Kalteyer, William Henermann, and J. C. Howard, all of San Antonio. Uriah Lott was the principal promoter of the line, and Mifflin Kenedy was contractor for virtually all of the mileage built before 1900. Kenedy received his payment in stocks, bonds, and in the bonuses given the SA&AP, which included $102,950 from the citizens of Corpus Christi and $52,660 from the citizens of Bee County. Between 1885 and 1887 the railroad built 222 miles of track between San Antonio and Corpus Christi and between San Antonio and Kerrville. During the years 1887 and 1888 the SA&AP constructed 176 miles between Kenedy and Houston. An additional 172 miles were completed from Yoakum to Waco between 1887 and 1891. Three branch lines, Gregory to Rockport, twenty-one miles; Skidmore to Alice, forty-three miles; and Shiner to Lockhart, fifty-four miles, were also built in 1888 and 1889. By the end of 1891 the SA&AP was operating 688 miles of main track. On July 14, 1890, the railroad went into receivership with Benjamin F. Yoakum and J. S. McNamara named receivers. A financial reorganization was effected by the SA&AP without any sale of the property, and the receivership was lifted on June 16, 1892. The SA&AP was a competitor in many areas with various Southern Pacific lines and was acquired by the SP in 1892. In that year the SA&AP owned fifty locomotives and 1,388 cars and reported passenger earnings of $401,000 and freight earnings of $1,318,000. The Railroad Commission brought suit in 1903 for forfeiture of the SA&AP charter in order to compel the SP to divest itself of ownership because of violation of the law which prohibited common ownership by parallel and competing lines. As a result of the suit the SP sold its stock in the company, but was required to continue to guarantee the bonds of the SA&AP. In 1904 the railroad began an extension to the lower Rio Grande valley. However, it only built thirty-six miles of track between Alice and Falfurrias, where the SA&AP terminated for the next twenty years. By 1916 it owned eighty-six locomotives and 2,810 cars. In that year the company reported passenger earnings of $1,228,000 and freight earnings of $2,851,000. The Interstate Commerce Commission authorized the SP to regain control of the SA&AP in 1925, and the company was leased to the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway Company for operation. Under SP auspices, the SA&AP built 135 miles of track between Falfurrias and McAllen and between Edinburg Junction and Brownsville, which opened in 1927. With the completion of the lines into the lower Rio Grande valley, the SA&AP owned 859 miles of main track. In 1933 the company abandoned forty miles between Shiner and Luling, and in 1934 the remaining 819 miles of track was merged into the Texas and New Orleans Railroad Company. With the changes in transportation requirements, much of the former SA&AP has been abandoned. In 1994 remaining portions included the track between Giddings and Cuero, San Antonio and Gregory, San Antonio and Camp Stanley, Houston and Eagle Lake, and Brownsville and McAllen.