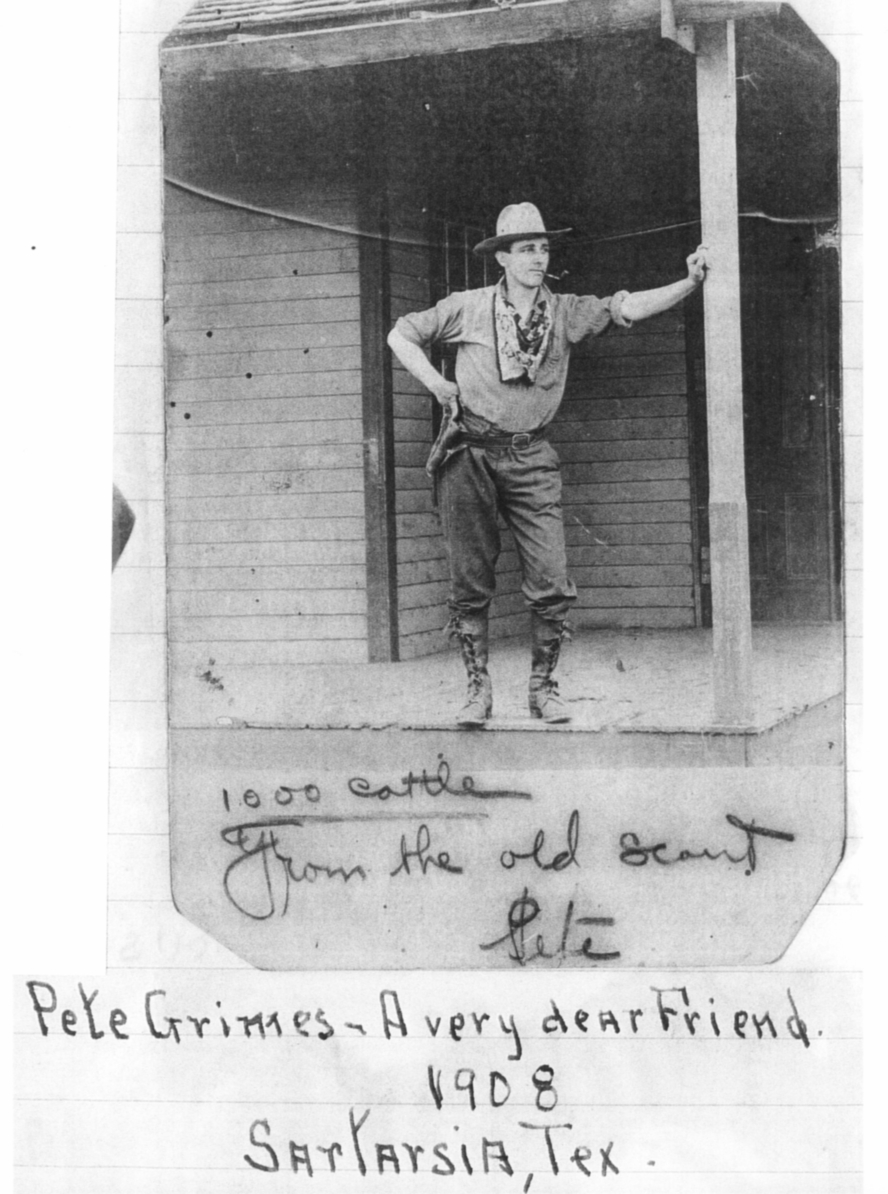

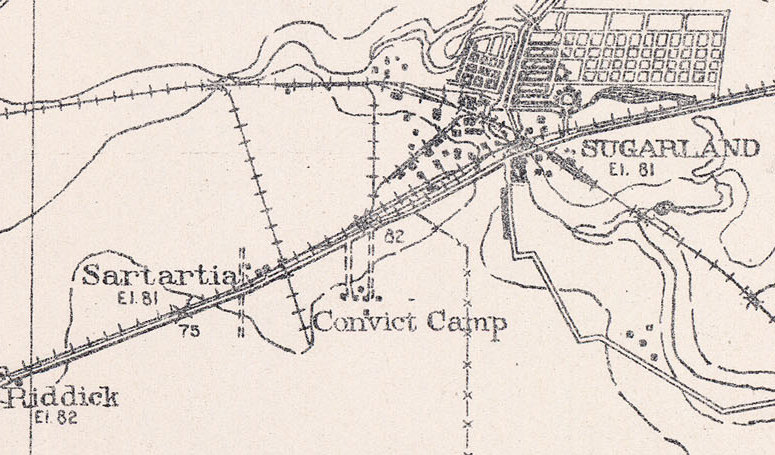

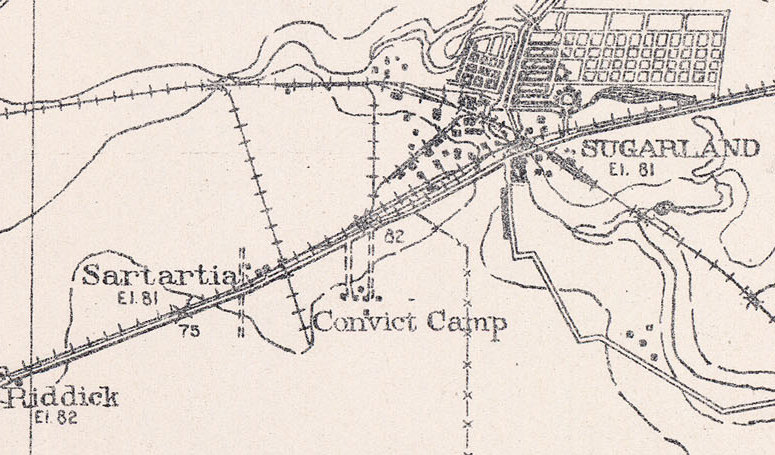

Sartartia, Texas

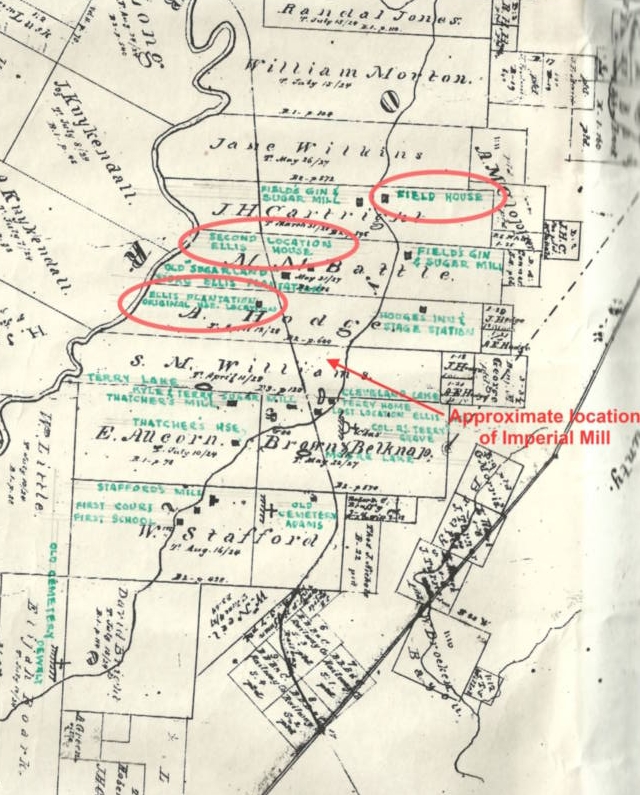

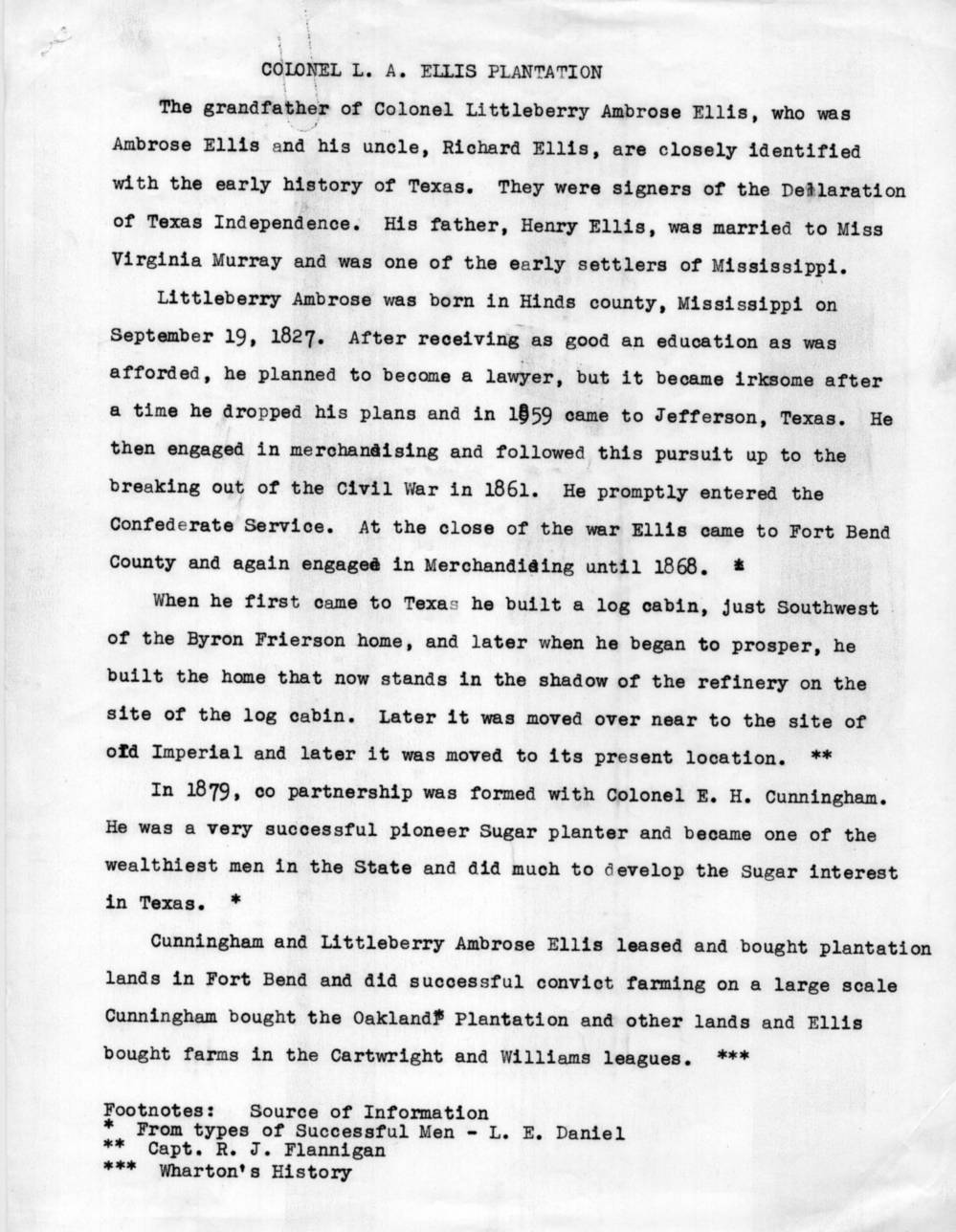

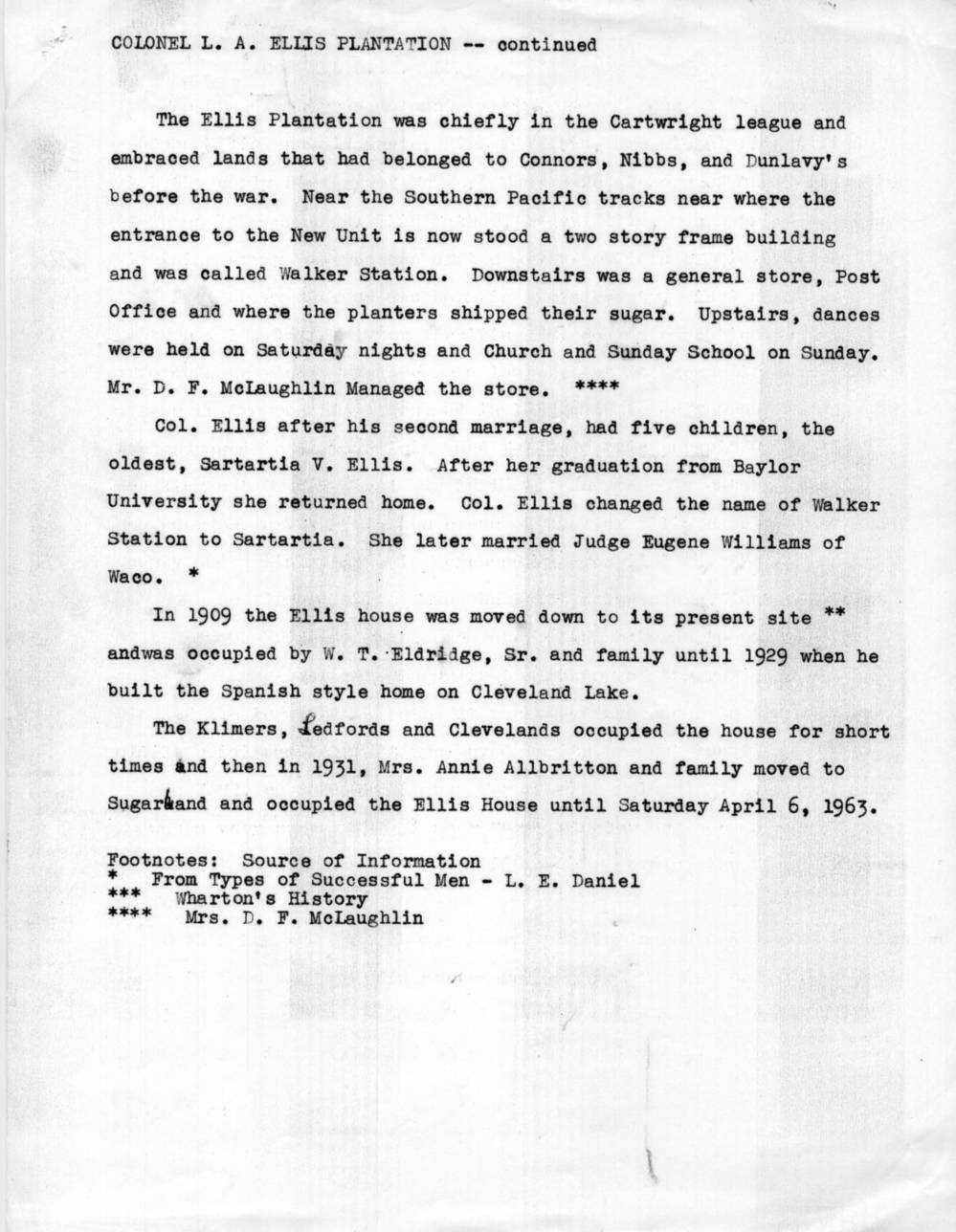

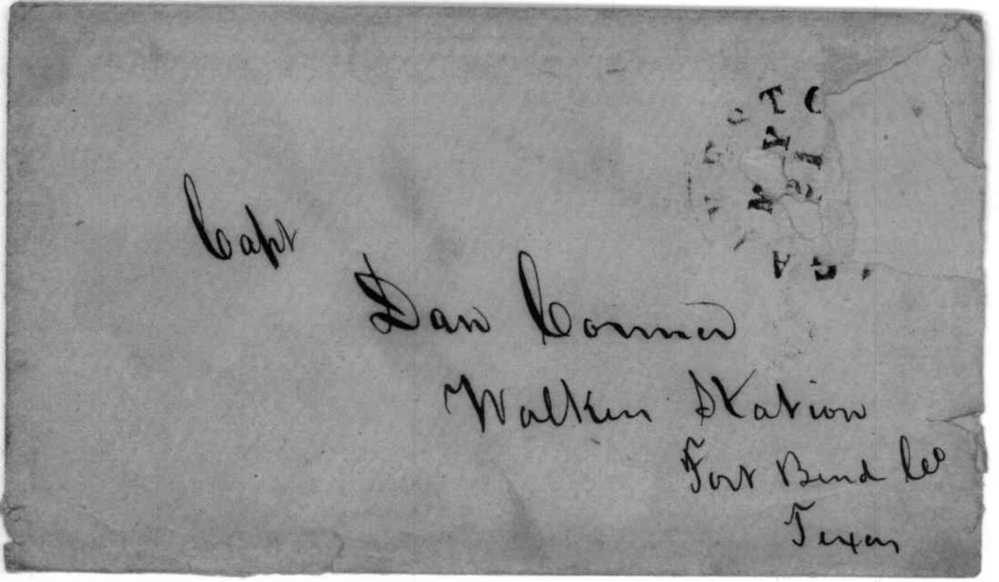

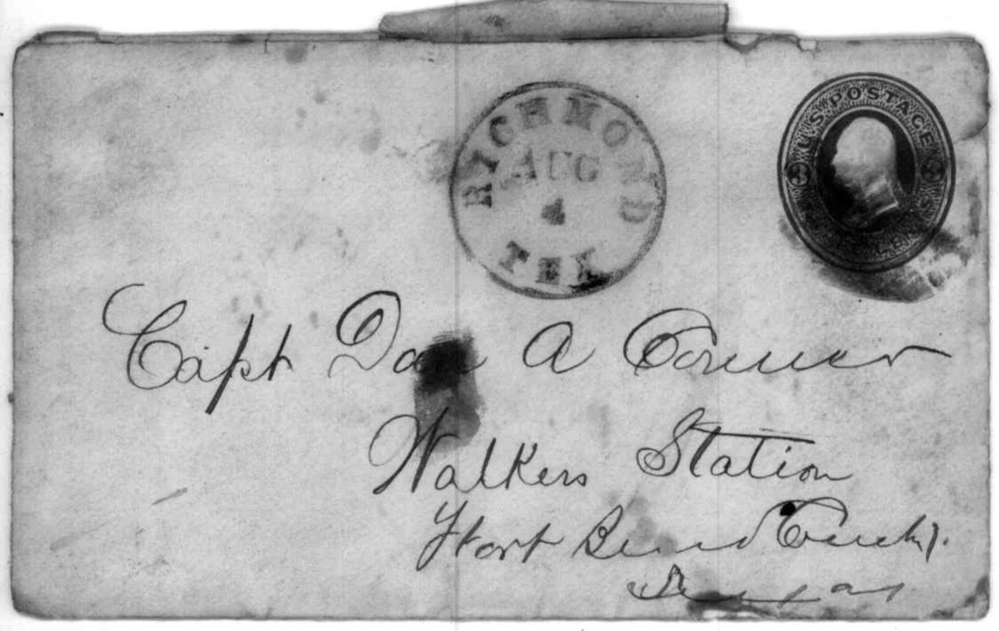

The book, "Sugar Land Texas and the Imperial Sugar Company" says that in l868, L. A. Ellis bought 2,000 acres of land out of the Mills Battle League and the Cartwright League, near Coldine Road. On the Southern Pacific tracks there was a station known as Walker Station, which had a two story building. Living quarters were upstairs with a post office and a general store down stairs. Ellis's purchase included this building, which he operated. He changed the name from Walker Station to Sartartia, after the first name of his oldest daughter. This was later part of the Central Unit of the Texas Prison System.

The book "TEXAS a guide to the lone star state" published in 1940 says; Sartartia Plantation covers a 2,000-acre tract devoted to the production of dairy stock and high grade milk. The dairy building, facing the highway, has large plate glass windows through which the operation of milking machines and the primary stages of milk handeling can be seen. The cattle barn, of sanitary modern construction, is cooled in summer and heated in winter. Part of the operation has been in continous operation since the days of slave labor.

Notes from Mark

Schumann about the “Walnut Plantation” article

January 24, 2010

The

following article “History of the Old Fields' Home 'Walnut Plantation'” was

written around 1943. The author is Mrs.

Boyd McCrary with the collaboration of Mrs. Emma McLaughlin

and Mrs. Paul Schumann.

I do not know who Mrs. Boyd McCrary is.

Mrs. Emma McLaughlin was Emma Fields, daughter of William Daniel and

Lucy Ann Fields. Mrs. Paul Schumann

refers to Lucille Fields, wife of Paul Ernest Schumann, daughter of Emma Fields

and D. F. McLaughlin.

The

Fields' Walnut Plantation was located near the bank of Oyster Creek, on the

north east quadrant where Oyster Creek crosses FM 1464, also known as Clodine

Road. The old plantation is now part of

the Orchard Lakes subdivision. The only

remnant of the plantation that remains today are the beautiful live oak trees

that were in it's front yard, which now grace a small park in Orchard Lakes.

The home

was still standing in the 1970s, but it was in poor condition. For decades, it had been used to store

hay. The roof was gone, the stairs and

floors were collapsing, all while children who lived nearby still liked to

explore the inside. My brother finally

demolished the house in the 1970s to avoid people getting injuries in the home. My uncle still has some of the bricks from

the house. These bricks were made by

slave labor from the clay along the banks of Oyster Creek, but were not sturdy

enough to withstand the passing of time.

The

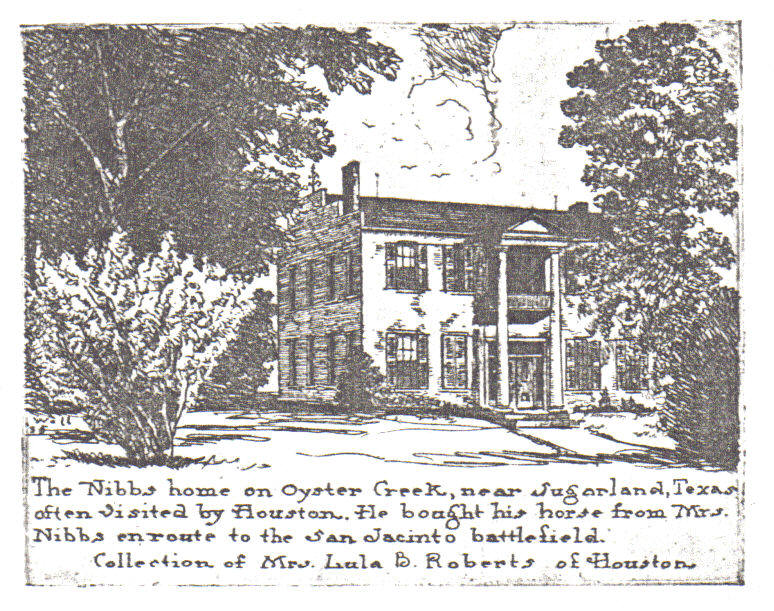

article references three sources, one of which is “Following General Houston”,

by B. Wall and A. Williams. I think this

is a rare book that can be found in the Fort Bend County Library. If it is the same book that I am thinking of,

this book has a very nice drawing of the plantation home, and it tells the

story of Sam Houston purchasing his white stallion from Mrs. Nibbs, only to

have the horse shot from beneath him in the Battle of San Jacinto. Many years ago, I saw the book at the library

and made photo copies of the pages that refer to this story, but I have been

unable to locate them.

The

article's style is a little crude in a couple of places where it refers to

African Americans, but I forgive that as

the style of the past.

History of the Old Fields' Home

“Walnut Plantation”

On the banks of Historic Oyster Creek, only a few miles north of the present Schumann-McLaughlin home on the Clodine-Sugar Land Road, stands the only remaining brick colonial house of pre-Civil War days that was built in Fort Bend County. To my knowledge there were only two such homes in Fort Bend; the old Churchill Fulshear house of Fulshear, which was razed about twelve years ago, and the old brick home of Walnut Plantation, the still stately walls of which stand, a poignant reminder of an era long since passed.

Built by slave labor of bricks, hand-molded of the creek-bank clay, of massive timbers, hand-hewn, fast approaching it's one-hundredth year, the childhood home of Mrs. Emma McLaughlin, then Emma Fields, the famous old home has remained in the Fields Family for over 59 years. It is now part of the Schumann-McLaughlin Plantation. But, shall we begin at the very beginning, and listen to –

“The small, dim noises, thousand-fold

That all old houses and gardens hold.”

...Stephen Vincent Benet

An interesting instance of how the plantation prospered in the early days is the case of Thomas W. Nibbs, an Alabama lawyer, who came to Texas in 1835 and tried his profession with little success. Dr. Johnson Hunter advised him to come to Oyster Creek and become a planter. He got together a few negroes and bought some land on credit from Jesse Cartwright, land granted to Cartwright by Stephen Austin. The first year he planted 9 acres of corn by making holes in the soil with a stick. He raised 900 bushels of corn. When he died a few years later, he had a large plantation and an increasing number of slaves, and his thrifty widow paid the debt off the plantation with one cotton crop.

Nibbs was the law partner of William Barrett Travis at the time of the tragic death of the latter at the Alamo. He was also a friend of Sam Houston, who visited often in the Nibbs home. While on his famous retreat, just before the battle of San Jacinto, Houston spent the night at the Nibbs home. Next morning he espied a fine white stallion in the corral and asked to buy the animal. Nibbs protested, saying the horse belonged to his wife, whereupon Houston passed the request to the rightful owner. In her enthusiasm for the Texan cause, Mrs. Nibbs consented to sell the animal, and the price was set at $300. Houston rode proudly away on the beautiful beast. When he led the charge of San Jacinto, this horse was shot dead from under him and at the same time he was severely wounded.

Nibbs did not live long after Texas became a republic. It was after his death that his widow, Mary Nibbs, built the brick home. The bricks were molded and burned on the creek bank with her own slave labor. The timbers were hand-hewn. The massive live-oaks, many of which still stand, are from the acorns she planted. The slave quarters were across the road.

Soon after the home was built, Mary Nibbs married the young law student and successor of her late husband, Judge C. W. Buckley. The plantation wealth of the Buckley's was assessed at $320,000, the second in the county at that time.

I should like to quote here from an article written in 1932 by Mrs. Lula B. Roberts of Houston, grand-daughter of Mary Nibbs Buckley. It tells the story of the old brick house in her own words:

“I can just remember the red brick house of my grandmother's cotton plantation. She owned 100 negro slaves.

The house was built in 1846, 15 years before I was born. It was beautiful. Its two stories contained 10 rooms. A wide hall ran through the center of the house. The stairs ran up at one side of the hall. There was a large room at the head of the stairs looking down on the back yard. The rooms were spacious, the ceilings high, the walls white plastered, and the fire-places with brass andirons were wide.

Brass candelabra with crystal pendants, were on each end of the parlor mantel and the floor was covered with Brussels carpet. The parlor suite was mahogany, upholstered in black horse-hair. An oval shaped white marble table stood in the center of the room. A beautiful pier-glass in a gilt frame hung on one wall, a portrait in oil of Grandmother and her second husband hung from another.

The house was colonial style with fluted columns. The Veranda railing was white. Down the broad steps a brick wall led to the gate. The flower garden was enclosed with a picket fence. No fowls were allowed in the garden but peacocks. They strutted up and down the brick walk in the sun, and their strident cries could be heard a mile away.

In front of the gate ran the road, and straight on down the embankment was Oyster Creek. Across the creek was Grandmother's cotton gin and sugar mill. Here she ginned her cotton and her neighbor's. On one side of the house were the old slave quarters, and the overseer's house. On the other were the new quarters. At the rear of the house were the quarters for the house servants, the barns, stables, poultry house and pigeon house. Farther on, quite a distance from the house, was the family burying ground, a lovely spot where Grandmother's first husband was buried.

Gay were the times in the brick house. The elite of Houston visited there for days, sometimes for weeks. The house rang with youthful laughter. Horseback riding and rambling through the wooded creek-banks by day, dancing by night. But the gay times passed. Sorrow came to the brick house – and death. One of the tragedies was the death of Judge Buckley, Grandmother's second husband. He maintained a law office in Richmond and had been attending court. Rain poured all day and the Brazos River was swollen. When he attempted to return home that night, his horse slid down the embankment into the river. His body was found three days afterward, and he too found rest in the family burying ground.

Other deaths occurred, and in the footsteps of sorrow came the War between the States. Grandmother was ruined. She not only lost her slaves, but all her crops. The Yankee soldiers came to the brick house. They helped themselves to everything in the storeroom. The sat in the parlor and spat on the Brussels carpet.

I was five years old when the brick house was sold. Strangers came to live there; other children to play under the trees. Relatives and friends have most all passed away. Very few are left, but strange to say, the brick house is still standing, 85 years old (this was written 11 years ago), although it is terribly changed with time …... Life seems but a dream.”

Walnut Plantation changed hands many times in the next years. Then in 1884 it was bought by W. D. Fields. (18 years – 8 transfers)

William Daniel Fields and Lucy Ann Yeater were born in Jefferson County, Kentucky, about 20 miles from Louisville. They were married quite young and for a while they made their home in Indiana. In 1858 they moved to Grayson County, Texas, and bought 500 acres of land near Sherman. Mr. Fields raised cattle, sheep, and some corn. During these days the Indians often raided Cook and Mantague Counties and Mr. Fields accompanied several expeditions against them.

In the Fall of 1859, he was in the Wichita Mountains. It was an exceptionally dry year and Red River and its tributaries were dry for 100 miles around. But around the mountains were fine springs. The buffalo were traveling south and had to stop for water at these springs. The whole country was black with them, and from the top of the mountain 30,000 buffalo could be seen, as nearly as could be estimated.

William Daniel and Lucy Ann Fields lived in Grayson County for four years. It was there daughter Emma was born. At the close of the Civil War they came to Fort Bend County and bought the Pat Perry place, lock, stock and barrel, which is now the Richardson farm. Before coming to Fort Bend, very progressive and enterprising, Mr. Fields had put into practice his idea of subsoiling. One very dry year he made fifty bushels to the acre while other farmers made only two. He took a government contract to furnish the United States troops at Fort Washita and Fort Arbuckle with $20,000 worth of corn. This he did. After the Civil War broke out, he purchased cattle for the Confederate Army. At the close of the war he came to Houston and bought cotton and shipped it to New York and Boston. He made quite a little fortune at this, but lost many head of cattle the following year on a drive to Kansas. It was then he came to Oyster Creek and turned planter. He raised sugar cane and cotton, had his own gin and sugar mill, where brown sugar and syrup were made. His syrup was famous throughout the country. Fort Bend County histories record that for years “.... he made the best syrup in this section of the state”.

In 1884 his own gin and sugar mill were in bad condition, so he bought nearby Walnut Plantation from the Kyles, lock, stock and barrel, even to the home-made lard and home-cured bacon. Suffice it to say that he was far more interested in the cotton gin and sugar mill than in the lovely old brick home, but it must have been of supreme interest to the five young Fields daughters. Miss Emma, at this time, was in Christenberg, Virginia, a select young ladies' school in the heart of the Allegheny Mountains.

There were 5000 acres in the plantation and over 300 negro tenants. The little darkies brought the lunches for the field hands, and when the plantation bell rang at noon the hands unhitched their plows, draped the harness over the backs of the mules and came to the big house to sit under the oaks and eat their lunches while the teams fed and watered. The cotton gin hummed in the fall and the sugar kettles boiled to the haunting melody of negro spirituals. Mr. Fields rode over the farm each day and the stump of the tree where he always tied his horse still stands.

The old brick house must have rung again with laughter and gay times when the Fields girls were all at home. But these were hard years too, the twenty dark years of Fort Bend History, when the county was under Carpet Bag and Negro rule. Clarence Wharton gives you a vivid picture in one sentence when he says: “Poor Fort Bend, with her 1600 white votes and 5400 colored.” I shall not go into this phase. Mr. Wharton's 12the chapter gives it more completely and concisely than I could. Mr. Fields, with other prominent planters in the country, organized and began to battle for white rule and after twenty years gathered enough Democrats to change the tide.

There were two weddings in the home itself and Miss Emma went from the home to the little church in Richmond where she was married to D. F. McLaughlin. This was on the day of the famous convention when the planters elected their own sheriff. The convention adjourned at dusk and everyone went to the wedding. After the reception many of the guests went to a mass meeting.

During the wedding trip Mrs. McLaughlin's father was burned while working in his sugar mill. Mr. McLaughlin took over the managing of the plantation for him until he recovered. The young couple then moved to the cottage across the creek (it still stands) and lived there for three years. It was here that their daughter Lucille was born. After three years they moved to Houston. Mr. Fields grieved to see them go and always hoped they would come back to the plantation, but Mrs. McLaughlin said she was “so thrilled to move to the city!” So they never returned.

I quote from Sowell's History of Fort Bend:

“Richmond, Texas, January 15th, 1902. Colonel W. D. Fields, of Sartartia, died this morning at 11:25 of pneumonia. Mr. Fields is one of the largest planters in this county; has lived near Sartartia for 35 years; was for four years county commissioner; for years made the best syrup in this portion of the state. The funeral will take place tomorrow at 2 P.M. At the family residence. Interment at the Hodge Bend Burial Ground.”

Walnut Plantation was left to his wife and children. Mrs. Fields lived here until her death. The children had scattered, had homes and lives of their own in other places, so tenants moved into the beautiful old home. The years, the storms have taken their toll. The roof is gone. The thick old slave-built walls have splayed out from the floor, (modern architects say that the old hand-made bricks and massive walls lack the resiliency to be pulled together), but the walls still stand, a mute testimony of other days.

“Not a log in this building but its memories has got,

And not a nail in this floor but touches a tender spot.”

…..Will Carleton.

Written by Mrs. Boyd McCrary

with the collaboration of Mrs. Emma McLaughlin

and Mrs. Paul Schumann

References: Sowell's History of Fort Bend County

Wharton's History of Fort Bend County

Following General Houston, by B. Wall and A. Williams

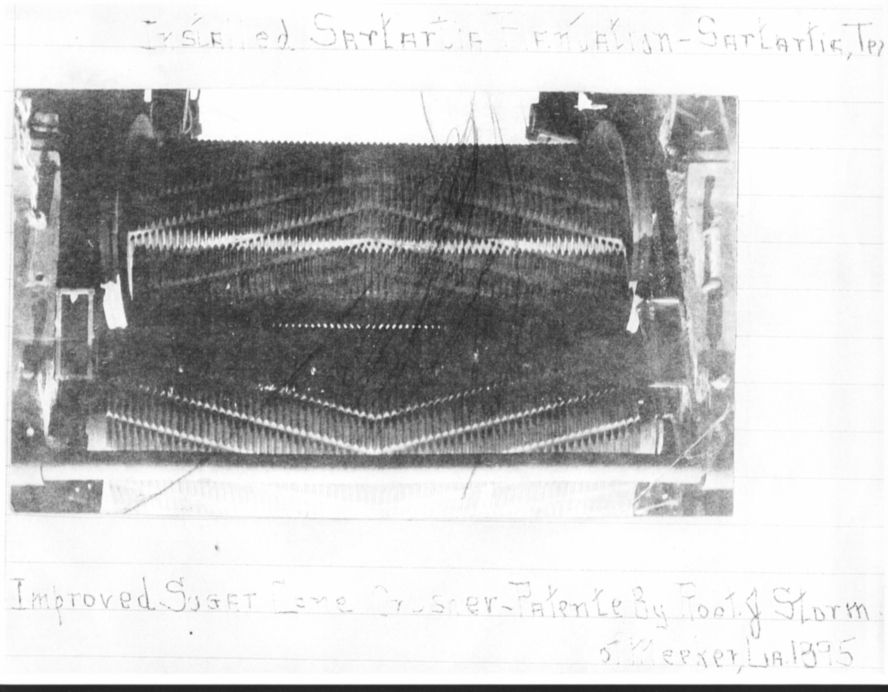

Writings at the top; Installed Sartartia, F .fntatign[sp] Sartartia, Tx.

Writings at the bottom; Improved sugar cane crusher. Patened by Root J. Storm of Meeker, La.

.